17 February 2026

Lotte krull

When performing calculations in a quantum computer qubits are required. Qubits are the units that enable the computer to perform calculations.

Qubits are produced in many different ways. Some use an atom or an electron, others utilise photons (light particles), and then there are those that create quantum bits using, for example, electricity and a special composition of materials.

"The ideal quantum bit is a quantum mechanical system over which we have 100% control. This means that we can control its state, and when we place it in a state, it does not change on its own. In addition, it must be possible to measure its state after a calculation with great precision, otherwise it would not be possible to obtain an understandable result from the quantum computer," explains Thomas Sand Jespersen.

He is a professor at DTU Energy where he researches quantum materials and develops solutions that ensure that quantum technologies can be connected to our classical electronics outside the quantum computer.

New type of quantum bit in crystals

Thomas Sand Jespersen says that it is still unclear which type of qubit will be the best solution for the quantum computer. In other words, the search for the perfect qubit is still ongoing.

”It’s still relevant to look for and investigate qubits in completely new places. This is one of the things we are currently working on in my group together with a consortium of European research groups from Italy, France, Sweden and Poland,” says Thomas Sand Jespersen.

Finding new solutions for quantum bits is not easy, says the professor, who explains:

“The function of a qubit will always be a compromise between different conditions. For example, a qubit that is very isolated from its surroundings will be able to maintain its state for a very long time. That is good, but on the other hand, it becomes correspondingly difficult to read the state of an isolated qubit.”

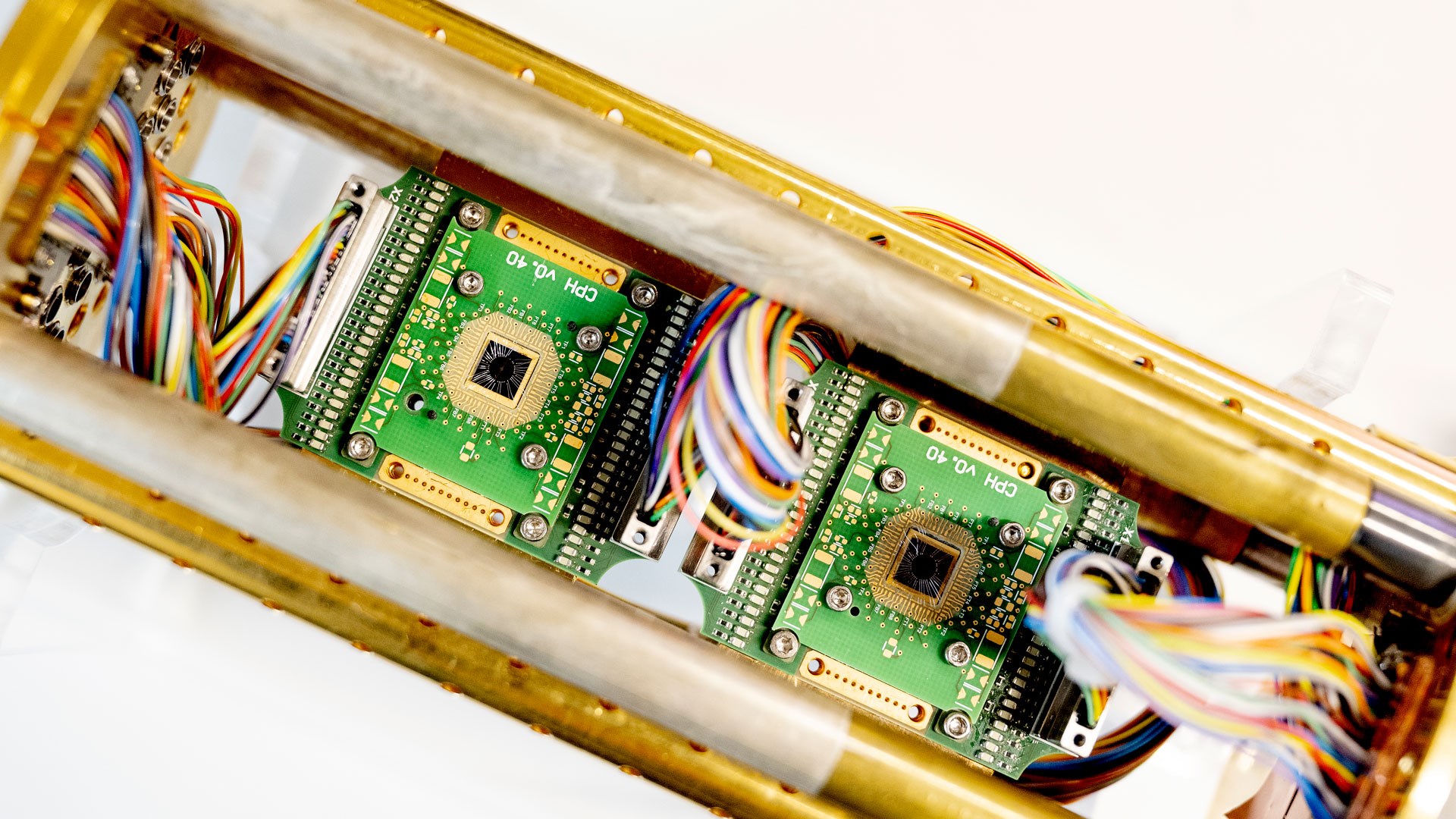

The new qubit that DTU researchers are currently investigating has been found in a type of material that belongs to the category of complex oxides.

Complex oxides are crystals that occur naturally and can be extracted from the earth. Today, they are used in jewellery and as crucial building blocks in energy technologies such as batteries and fuel cells.

They can also be grown artificially, which means that you can have your own crystal production. The Functional Oxides section at DTU Energy is one of the world's leading groups in the production of these materials and has extensive facilities for oxide cultivation at the Lyngby Campus.

"It’s still relevant to look for and investigate qubits in completely new places."

Professor Thomas Sand Jespersen DTU Energy

Materials with unique properties

A complex oxide has a relatively complicated crystal structure and typically contains several elements. One of these is oxygen, as revealed by the word ‘oxide’. They are already widely used in energy technology, and research into oxides has a long history at DTU Energy.

But it turns out that they also have some unique electronic properties at low temperatures, which makes them interesting for quantum technology and qubits. Right now, DTU researchers are looking at strontium titanate, because the material is exotic, as the professor puts it.

"Strontium titanate is what we call a quantum material. This means that we cannot avoid using quantum mechanics if we want to describe its properties. The material is highly interactive. This is evident, for example, in the fact that it entangles the movement of electrons with crystal vibrations, which means that the electrons can really sense each other and react as a group. Imagine a flock of starlings. When one changes direction, the whole flock follows. The electrons in this material do the same. This makes it more complicated to understand and control, but it also opens up new possibilities," says Thomas Sand Jespersen.

He explains that, in comparison, the electrons in other materials, such as silicon, which is often used in quantum technology, are fairly indifferent to each other – they simply follow their own path and prefer to continue undisturbed.

Faster quantum computers

The advantage of the eager electrons in strontium titanate is that they can – perhaps – be used as qubits, with new methods for controlling and reading their state.

“If we succeed in utilising the electrons in strontium titanate, we may be able to create new qubits that can work much faster in a quantum computer,” says Thomas Sand Jespersen, adding:

“So far, it looks promising.”