JUNE 1, 2018

By Ben Brumfield

Curvy baseball pitches have surprising things in common with quantum particles described in a new physics study, though the latter fly much more weirdly.

In fact, ultracold paired particles called fermions must behave even weirder than physicists previously thought, according to theoretical physicists from the Georgia Institute of Technology, who mathematically studied their flight patterns. Already, flying quantum particles were renowned for their weirdness.

To understand why, start with similarities to a baseball then add significant differences.

Wave matter

An artist's depiction of what a group of atoms looks like when they merge to a wave-like state. This occurs under ultra-cooling that drops atoms' temperature to near absolute zero, the coldest possible temperature in the universe. This is not an image of something done in this Georgia Tech study but is intended to help readers picture the particle-wave duality the study considers along with other factors.

Credit: NIST National Institute of Standards and Technology / press image

A pitcher imparts spin, momentum, and energy to a baseball when throwing a curveball, a change-up, or a slider. Fermions’ funny flights are likewise carved by spins, momenta, and energies, but also by powerful quantum eccentricities like entanglement, which Albert Einstein once called “spooky action at a distance” between quantum particles.

In the new study, the researchers even predicted that the particles can act like different quantum balls called bosons to mimic the manner that photons, or particles of light, fly. A simplified explanation of these ultracold paired particles and their odd flights is below.

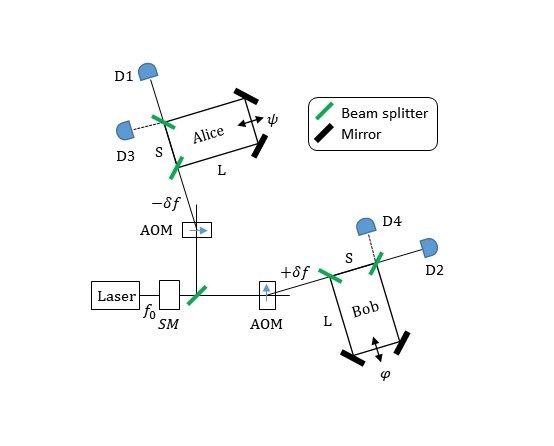

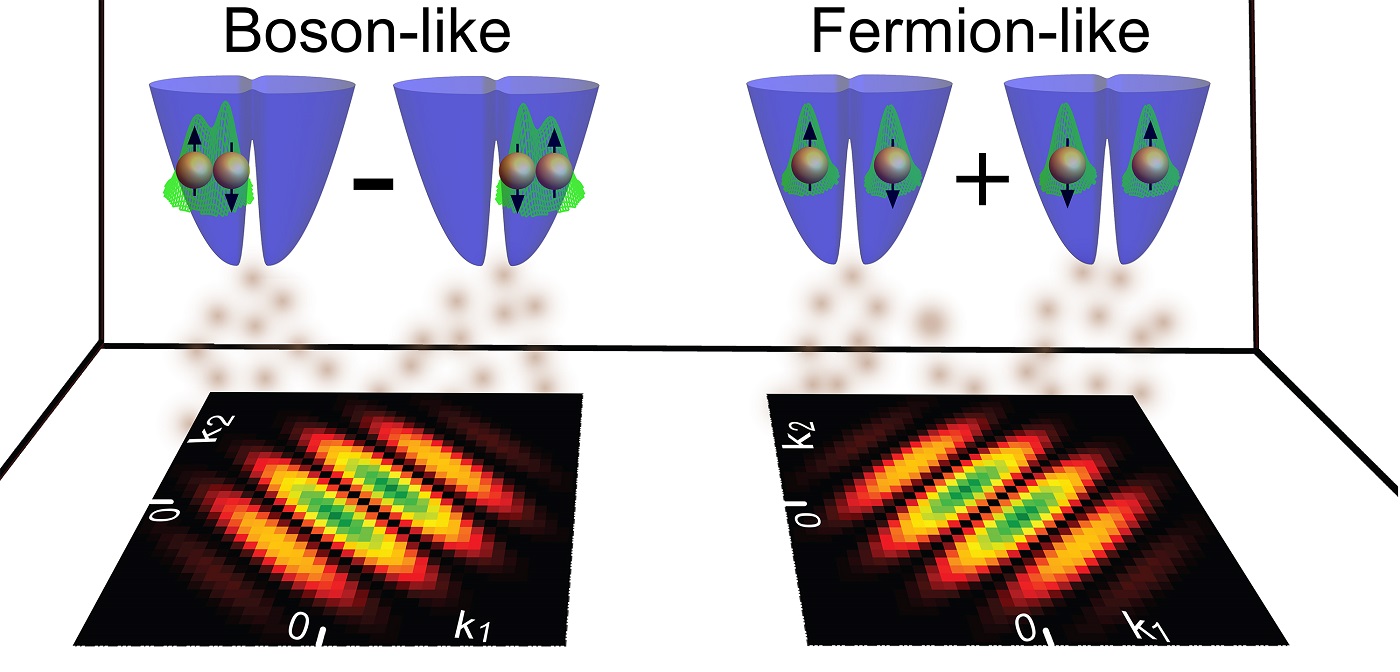

Trapped ultracold fermions in double-wells

The top row illustrates a ground state boson-like (paired, i.e. bunched) configuration of two ultracold atoms trapped in a double-well potential on the left, and on the right, a fermion-like (unpaired, or anti-bunched) configuration of the two atoms. The atoms are represented by balls with the atoms’ spins indicated by the up and down arrows. The wave functions corresponding to the atoms are superimposed on the atoms.

In the bottom row, we show the theoretically predicted two-atom momentum (denoted as k1 and k2) correlation maps corresponding to the configurations in the top row. These momentum correlation maps, which contrast in the two cases shown here, could be measured in laboratory experiments when the double-well trapping potentials are turned off, and the results can be used to fully characterize the flights taken by the two atoms for each of the starting configurations. Such information, uncovered by the theoretical calculational modeling of Georgia Tech physicists, are targeted at aiding the design and analysis of ultracold atom experiments aiming at revealing the quantum nature of ultracold matter.

Credit: Georgia Tech / Uzi Landman

Light-matter modeling

Those influences all combine to give fermions a trajectory repertoire much odder than that of any master baseball pitcher, and the new study maps it out and opens new ways to observe it experimentally. The Georgia Tech team took the offbeat approach of adding quantum optical -- or light-like – ideas to their predictive calculations of these specks of matter and arrived at eyebrow-raising, insightful results.

“The particle behavior we predicted is just schizophrenic,” said Uzi Landman, Regents’ and Institute Professor and F.E. Callaway Endowed Chair in Georgia Tech’s School of Physics.

Mathematical and theoretical details can be found in the study in the journal Physical Review A, which Landman, first author Benedikt Brandt, who is a graduate research assistant, and senior scientist Constantine Yannouleas published on May 4, 2018. Their research was funded by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research.

particles gone to wave form

Particles such as atoms bounce around chaotically, but when ultracold, they take on wave behavior, as illustrated in this figurative artist's depiction of their behavior. The image is not part of the study done at Georgia Tech but serves to help readers visualize the particle-wave duality of matter that the study also considers.

Credit: science@NASA

Flying fermions explained

Tracing quantum curveballs is counterintuitive by nature with concepts like fermions, bosons, spins, spooky entanglement, and particle-wave duality. So, let’s go step-by-step to understand them and the study’s insights.

The ballgame revolves around fermion pairs. Fermions can be subatomic particles or whole atoms. In this case, the physicists modeled using atoms.

The term fermion refers to quantum-statistical properties that the particle has as opposed the properties of its counterpart particle called a boson, in particular the particle’s spin, which is called half-integer for fermions and full-integer for bosons. (These spins aren’t exactly like those on a ball. For more, see: Fermions and Bosons for Dummies.)

"Photons and Higgs bosons are examples of bosons," Landman said. "Bosons are gregarious: Two or more bosons can share the exact same space. This allows many of them to be superimposed onto each other on the same tiny spot."

"Fermions, on the other hand, are standoffish. They lay claim to their own space, and don't share it with other particles. Fermions can be stacked upon each other but do not occupy the same space."

Electrons, protons, neutrons, and some atoms are common examples of fermions.

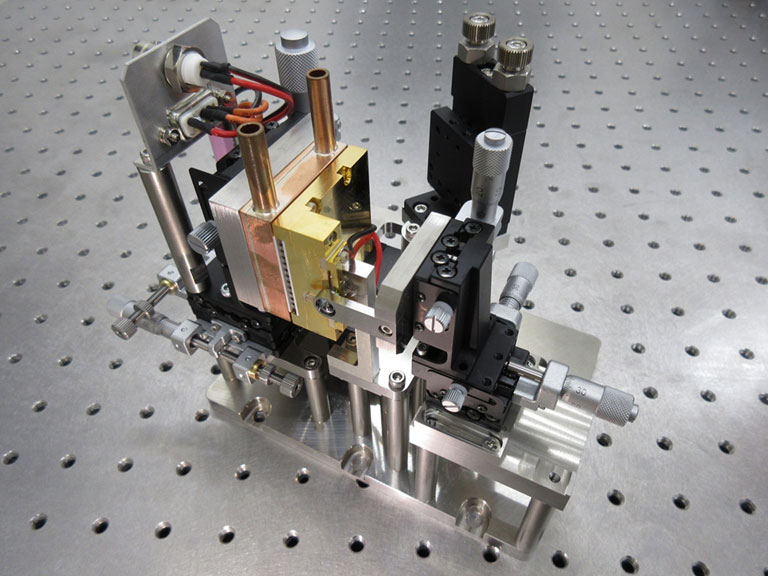

Physics Regents' Professor Uzi Landman

For a week, 900 processors ran parallel to calculate possible flight patterns of pairs of quantum particles called fermions for a new theoretical physics study on ultracold matter. Principal investigator Uzi Landman, is Regents’ and Institute Professor and F.E. Callaway Endowed Chair in Georgia Tech’s School of Physics. Here, he stands between racks of computers at a Georgia Tech computer farm. To arrive at their final calculations, the team employed roughly the same amount of computing power for nearly four months. Credit: Georgia Tech / Allison Carter

Laser-tweezing baseballs

The theoretical study envisions two fermionic atoms starting out carefully held next to each other by two pairs of “tweezers” made of intersecting laser beams, as is actually done in applicable physics experiments. In the study's theoretical setup, lasers and special magnetic fields would also be used to slow the fermions to a near halt, making them “ultracold” at 0.000000001 degrees Kelvin, or -273.15 degrees Celsius (-459.67 degrees Fahrenheit).

That’s a sliver above absolute zero, the lowest possible temperature in the universe, and particles that cold do strange things.

“A particle’s motion is usually frantic, but the cooling slows it down almost to a stand-still,” said Landman, who is also director of the Georgia Tech Center for Computational Materials Science. “And these particles also have wave properties, and at that temperature, the wavelength grows enormously long.”

“The waves become microns in size. That would be like a pebble growing to be a third of the size of this country. When that happens, the atom actually becomes visible under an optical microscope.”

The inflated size makes it easier for researchers to know the two particles’ starting locations. When they turn the laser tweezers off, the fermions fly away. The particles’ wave properties also have a lot to do with their weird flights.

“A particle in motion will act as a projectile under certain circumstances. But in others, it will behave like a wave,” Landman said. “We call it the quantum world duality.”

Together or apart

“If you set up two detectors at different positions but the same distance from the particle pair, how often the two fly into the same detector or how often they fly into separate ones says a lot about those particles,” Landman said. “And that’s where our weird findings come in.”

Fermions are expected to fly differently from bosons, but the theoretical physicists’ study on fermions revises this idea. Depending on the degree of quantum entanglement between the two fermions before they’re released and depending on their energy level, they can act like fermions or act like bosons.

“This adds new weirdness to the already established schizophrenic particle-wave duality,” Landman said.

“A pair of photons (which are bosons) fly to the same place. They stay as a pair,” Landman said. “They’re social animals, and you find them either both in the one detector or both in the other. We call this phenomenon ‘bunching.’”

Weirdo flight paths

Fermions are often expected to do the opposite, referred to as anti-bunching, but according to the study, how they fly depends on whether or not they have spooky interaction and, if so, whether the interaction is attractive or repulsive.

“If they’re interacting, and depending on the starting energy level, we predict that they may do strange things when they fly,” Landman said. “That’s new.”

“At the base energy level, called ground state, our two fermions that interact with ultra-strong repulsion behave fermionically, meaning they avoid each other. Now, if they interact with strong attraction, they aggregate the way bosons do,” Landman said. “So far, all as expected.”

But bumping up the trapped particles’ level of energy, or excitation, via an additional laser or a magnetic field, would appear to heighten the particles’ weirdness. The excitation levels can twist the rules of what interactions do to a fermion’s flight, according to the theoretical study.

For example, the above mentioned fermionic behavior usually connected with strong repulsive interaction could turn bosonic, according to the physicists’ calculations. In other words, the two particles would fly to the same detector the way bosons do.

Orderly quantum schizophrenia

“As crazy as all this looks, there appears to be strong reliability in these behaviors that could even be predictably and practically manipulated,” Landman said.

As with a pitcher who finesses a screwball’s path, physicists could determine a fermion’s weird flight using quantum mechanical formulation, advanced computational simulation, and experimentation, the study said.

“It looks like you may even be able to engineer what this quantum weirdness does,” Landman said. "If you know particle states reliably, you may be able to use them as a resource for quantum computations and information storage and retrieval."

Like this article? Get our email newsletter here.

The research was funded by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (award # FA9550-418 15-1-0519). Findings and opinions are those of the authors and not necessarily of the sponsoring agency. Georgia Tech's Brice Zimmerman contributed baseball background to this report.