November 29, 2017

Two independent teams of scientists, including one from the Joint Quantum Institute, have used more than 50 interacting atomic qubits to mimic magnetic quantum matter, blowing past the complexity of previous demonstrations. The results appear in this week’s issue of Nature.

As the basis for its quantum simulation, the JQI team deploys up to 53 individual ytterbium ions—charged atoms trapped in place by gold-coated and razor-sharp electrodes. A complementary design by Harvard and MIT researchers uses 51 uncharged rubidium atoms confined by an array of laser beams. With so many qubits these quantum simulators are on the cusp of exploring physics that is unreachable by even the fastest modern supercomputers. And adding even more qubits is just a matter of lassoing more atoms into the mix.

“Each ion qubit is a stable atomic clock that can be perfectly replicated,” says JQI Fellow Christopher Monroe*, who is also the co-founder and chief scientist at the startup IonQ Inc. “They are effectively wired together with external laser beams. This means that the same device can be reprogrammed and reconfigured, from the outside, to adapt to any type of quantum simulation or future quantum computer application that comes up.” Monroe has been one of the early pioneers in quantum computing and his research group’s quantum simulator is part of a blueprint for a general-purpose quantum computer.

Quantum hardware for a quantum problem

While modern, transistor-driven computers are great for crunching their way through many problems, they can screech to a halt when dealing with more than 20 interacting quantum objects. That’s certainly the case for quantum magnetism, in which the interactions can lead to magnetic alignment or to a jumble of competing interests at the quantum scale.

“What makes this problem hard is that each magnet interacts with all the other magnets,” says research scientist Zhexuan Gong, lead theorist and co-author on the study. “With the 53 interacting quantum magnets in this experiment, there are over a quadrillion possible magnet configurations, and this number doubles with each additional magnet. Simulating this large-scale problem on a conventional computer is extremely challenging, if at all possible.”

When these calculations hit a wall, a quantum simulator may help scientists push the envelope on difficult problems. This is a restricted type of quantum computer that uses qubits to mimic complex quantum matter. Qubits are isolated and well-controlled quantum systems that can be in a combination of two or more states at once. Qubits come in different forms, and atoms—the versatile building blocks of everything—are one of the leading choices for making qubits. In recent years, scientists have controlled 10 to 20 atomic qubits in small-scale quantum simulations.

Currently, tech industry behemoths, startups and university researchers are in a fierce race to build prototype quantum computers that can control even more qubits. But qubits are delicate and must stay isolated from the environment to protect the device’s quantum nature. With each added qubit this protection becomes more difficult, especially if qubits are not identical from the start, as is the case with fabricated circuits. This is one reason that atoms are an attractive choice that can dramatically simplify the process of scaling up to large-scale quantum machinery.

An atomic advantage

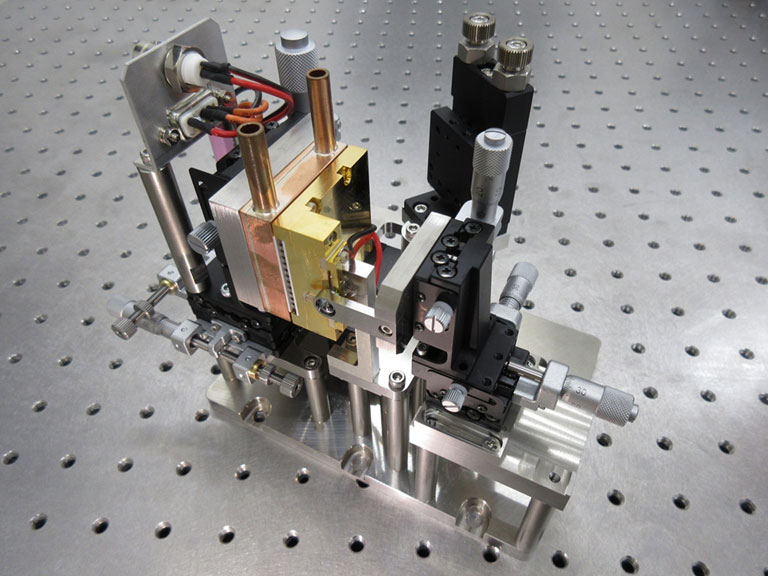

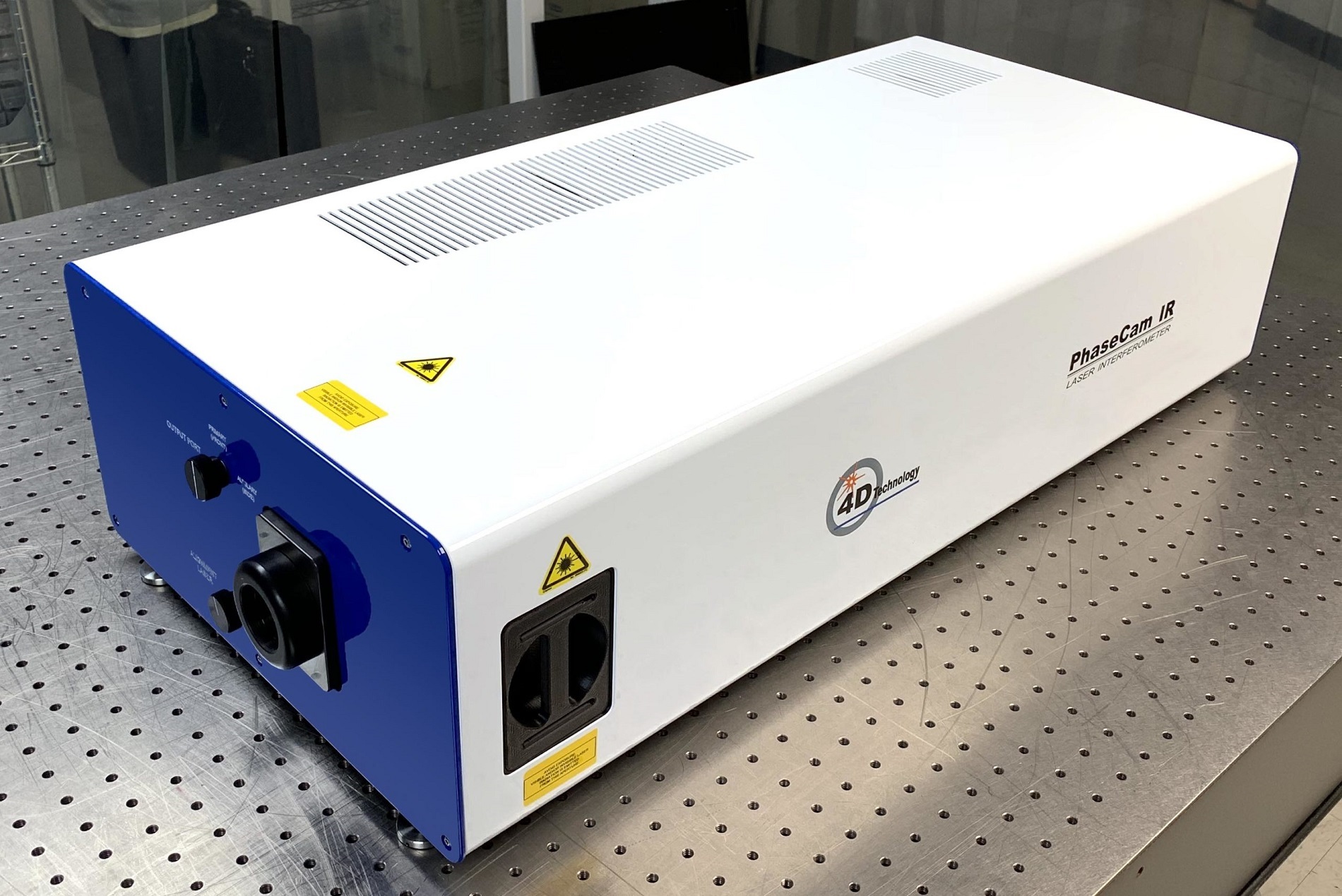

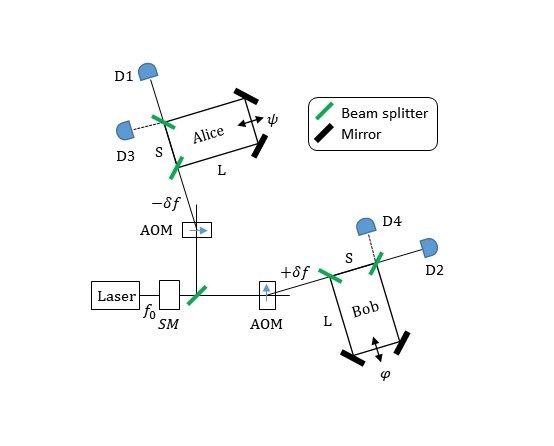

Unlike the integrated circuitry of modern computers, atomic qubits reside inside of a room-temperature vacuum chamber that maintains a pressure similar to outer space. This isolation is necessary to keep the destructive environment at bay, and it allows the scientists to precisely control the atomic qubits with a highly engineered network of lasers, lenses, mirrors, optical fibers and electrical circuitry.

“The principles of quantum computing differ radically from those of conventional computing, so there’s no reason to expect that these two technologies will look anything alike,” says Monroe.

In the 53-qubit simulator, the ion qubits are made from atoms that all have the same electrical charge and therefore repel one another. But as they push each other away, an electric field generated by a trap forces them back together. The two effects balance each other, and the ions line up single file. Physicists leverage the inherent repulsion to create deliberate ion-to-ion interactions, which are necessary for simulating of interacting quantum matter.

The quantum simulation begins with a laser pulse that commands all the qubits into the same state. Then, a second set of laser beams interacts with the ion qubits, forcing them to act like tiny magnets, each having a north and south pole. The team does this second step suddenly, which jars the qubits into action. They feel torn between two choices, or phases, of quantum matter. As magnets, they can either align their poles with their neighbors to form a ferromagnet or point in random directions yielding no magnetization. The physicists can change the relative strengths of the laser beams and observe which phase wins out under different laser conditions.

The entire simulation takes only a few milliseconds. By repeating the process many times and measuring the resulting states at different points during the simulation, the team can see the process as it unfolds from start to finish. The researchers observe how the qubit magnets organize as different phases form, dynamics that the authors say are nearly impossible to calculate using conventional means when there are so many interactions.

This quantum simulator is suitable for probing magnetic matter and related problems. But other kinds of calculations may need a more general quantum computer with arbitrarily programmable interactions in order to get a boost.

“Quantum simulations are widely believed to be one of the first useful applications of quantum computers,” says Alexey Gorshkov**, JQI Fellow and co-author of the study. “After perfecting these quantum simulators, we can then implement quantum circuits and eventually quantum-connect many such ion chains together to build a full-scale quantum computer with a much wider domain of applications.”

As they look to add even more qubits, the team believes that its simulator will embark on more computationally challenging terrain, beyond magnetism. “We are continuing to refine our system, and we think that soon, we will be able to control 100 ion qubits, or more,” says Jiehang Zhang, the study’s lead author and postdoctoral researcher. “At that point, we can potentially explore difficult problems in quantum chemistry or materials design.”

Written by E. Edwards

* Christopher Monroe is a fellow of the Joint Quantum Institute and the Joint Center for Quantum Information and Computer Science. He is a Distinguished University Professor & Bice Seci-Zorn Professor in the UMD Physics Department.

**Alexey Gorshkov is a fellow of the Joint Quantum Institute and the Joint Center for Quantum Information and Computer Science. He is an Adjunct Professor in the UMD Physics Department.

"Observation of a many-body dynamical phase transition with a 53-qubit quantum simulator," J. Zhang, G Pagano, P. W. Hess, A Kyprianidis, P. Becker, H. Kaplan, A. V. Gorshkov, Z-X Gong, Christopher Monroe, Nature, 551, (2017)