May 22, 2017

The quantum computer has fuelled the imagination of scientists for decades: It is based on fundamentally different phenomena than a conventional computer. Therefore, it is expected to work out problems in the not too far future which are virtually impossible to solve by classical supercomputers. Physicists refer to this as "quantum computational supremacy".

But the supremacy of quantum computers has yet to be proved: Using quantum mechanical effects for calculations is difficult, so previous prototypes were only able to solve very simple problems. Researchers from the University of Würzburg and from the Chinese University for Science and Technology in Hefei and Shanghai are prepared to change this. They just published their studies in the journals Nature Photonics and Physical Review Letters.

The scientists built a special variant of a quantum computer that is dedicated to a single task. "So we don't have a real universal quantum computer, but rather its little brother that is capable of solving one special problem only," Professor Sven Höfling from the University of Würzburg's Chair for Applied Physics explains.

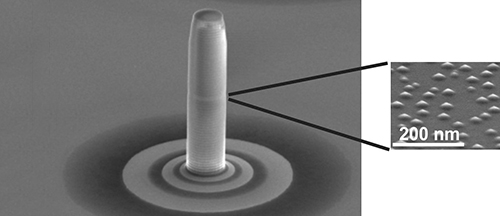

For years, Höfling and his colleagues Christian Schneider and Martin Kamp have worked on developing and improving a central element of this computer: a so-called single-photon source. This source generates individual light particles (photons) at the push of a button. In contrast, for a light bulb or a laser, it is impossible to predict exactly how many photons will be emitted at any given time.

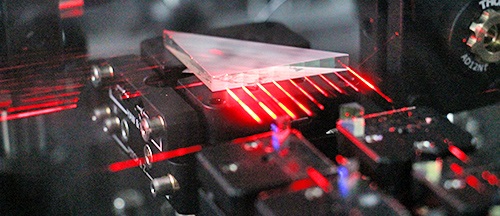

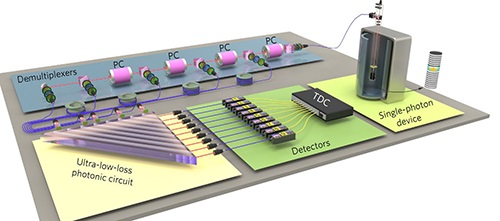

A photo of the test setup (photo: Chaoyang Lu/University for Science and Technology)

Basis of numerous quantum optics experiments

The Würzburg light source has yet another advantage: The emitted light particles look identical: They have exactly the same colour and propagate in the same direction. "Single photons as these are a basic requirement for many quantum optics experiments," Höfling emphasises. "We have optimised our methods during years of work so that we are now able to generate such light particles very efficiently and reliably." Expressed in figures this means that when the scientists push the button 100 times, their light source will produce a single photon up to 74 times. Only once does the method erroneously deliver two photons at the same time.

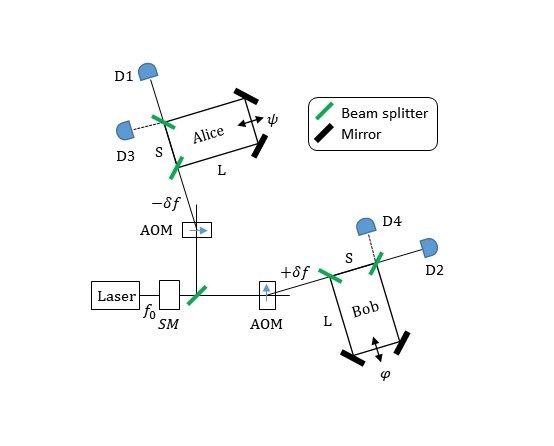

The partners from Hefei and Shanghai sent the photons out on a kind of optical orientation run: They made the light particles pass through a material where they came upon a fork in the road, figuratively speaking, at regular intervals. Then each time they had to choose either the left or the right path.

Their situation is similar to that of a man who tosses a coin several times in a row. He takes a step to the right each time the coin shows heads. If it comes up tail, he will walk a step to the left. After flipping the coin ten times, the man has probably not gotten very far from where he started since a coin has a 50/50 probability of landing tail or head. In order to go ten steps to the right, he would have to land heads up ten times in a row. And this is rather unlikely.

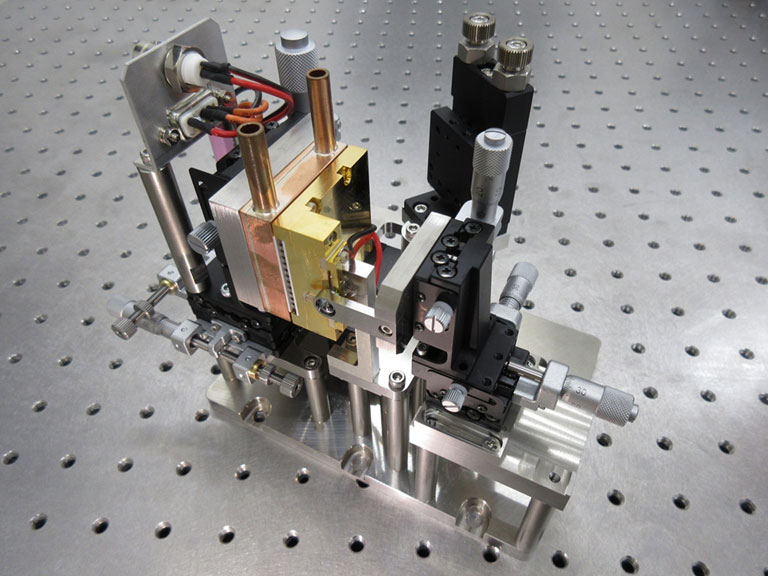

The single-photon source is shown on the right. (Graphic: Chaoyang Lu/University for Science and Technology)

A quantum walk with five participants

If this experiment was conducted 1,000 times in a row and the man's position was recorded after each toss, we would obtain a typical bell-shaped curve: The journey frequently ends somewhere near the starting point. In contrast, the man is only rarely located far on the left or right.

The experiment is called "random walk". We encounter this phenomenon in many areas of nature for example as the Brownian motion. Its analogy in quantum physics is the so-called "random quantum walk".

However, the outcome of this quantum walk is much more difficult to predict because of the quantum interference of undistinguishable particles, especially so when multiple particles set off at the same time.

"Already from about 20 photons, classical computers reach their limits" Höfling explains. "Our partners from China therefore use the single photons in connection with a photonic circuit for a quantum simulation which emulates the problem."

In the recent publications, they dispatched up to five photons simultaneously. To determine the distribution, they needed about as much time using their method as it would have taken the very first electronic computers to do. "But we are optimistic that our approach will enable us to run simulations with 20 or more photons," Sven Höfling says hopefully. "This would take us to a level where quantum technology could prove its supremacy over standard computers for the first time and we are working on this."

Hui Wang et al.: High-efficiency multiphoton boson sampling; Nature Photonics; DOI: 10.1038/nphoton.2017.63.

Yu He u.a.:Time-Bin- Encoded Boson Sampling with a Single-Photon Device; Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 190501 (2017)