2016-11-07

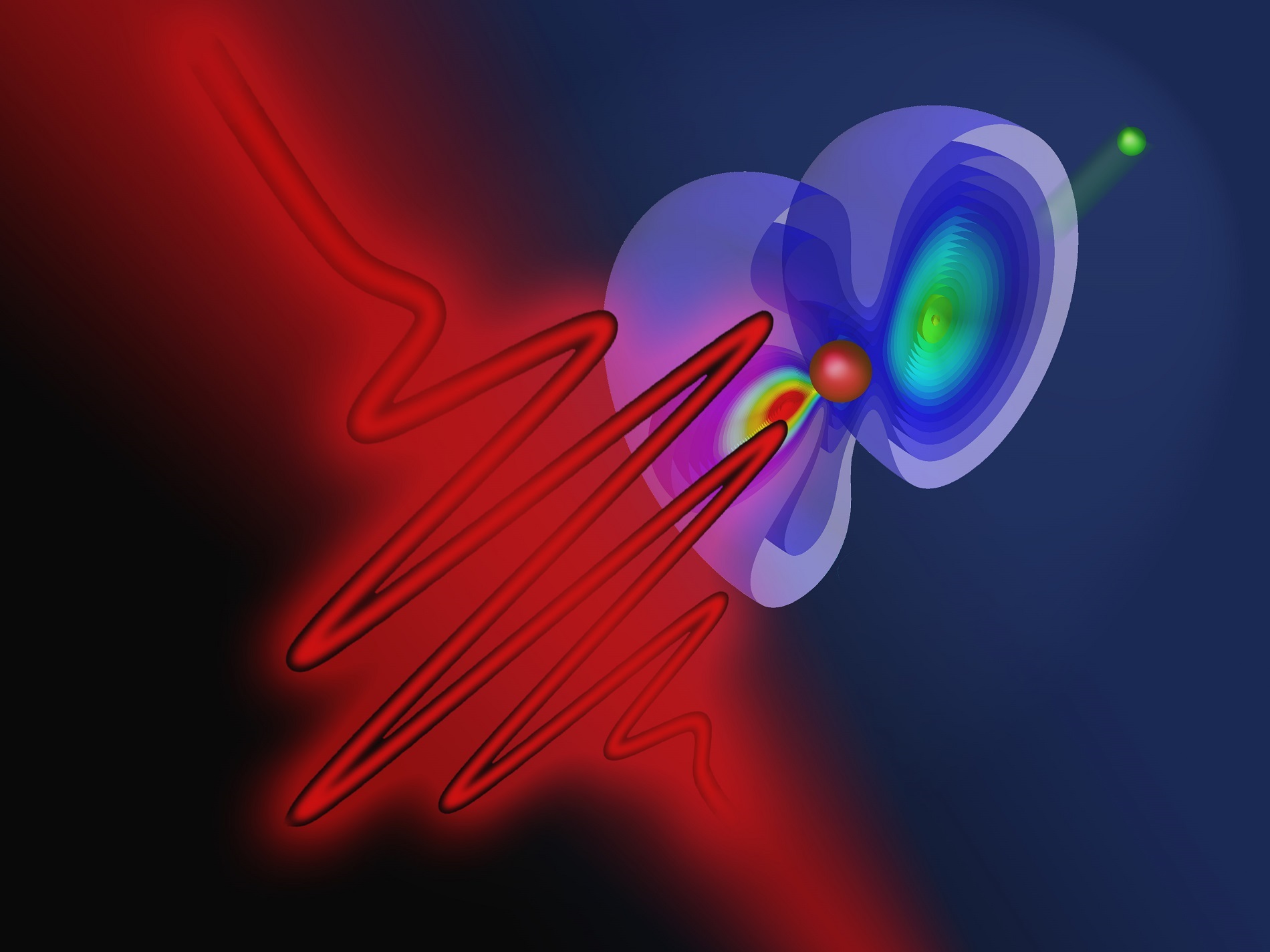

Quantum particles can change their state very quickly – this is called a “quantum jump”. An atom, for example, can absorb a photon, thereby changing into a state of higher energy. Usually, these processes are thought to happen instantaneously, from one moment to the next. However, with new methods, developed at TU Wien (Vienna), it is now possible to study the time structure of such extremely fast state changes. Much like an electron microscope allows us to take a look at tiny structures which are too small to be seen with the naked eye, ultrashort laser pulses allow us to analyse temporal structures which used to be inaccessible.

The theoretical part of the project was done by Prof. Joachim Burgdörfer’s team at TU Wien (Vienna), which also developed the initial idea for the experiment. The experiment was performed at the Max-Planck-Institute for Quantum Optics in Garching (Germany). The results have now been published in the journal “Nature Physics”.

The Most Accurate Time Measurement of Quantum Jumps

A neutral helium atom has two electrons. When it is hit by a high energy laser pulse, it can be ionized: one of the electrons is ripped out of the atom and departs from it. This process occurs on a time scale of attoseconds – one attosecond is a billionth of a billionth of a second.

“One could imagine that the other electron, which stays in the atom, does not really play an important part in this process – but that’s not true”, says Renate Pazourek (TU Wien). The two electrons are correlated, they are closely connected by the laws of quantum physics, they cannot be seen as independent particles. “When one electron is removed from the atom, some of the laser energy can be transferred to the second electron. It remains in the atom, but it is lifted up to a state of higher energy”, says Stefan Nagele (TU Wien).

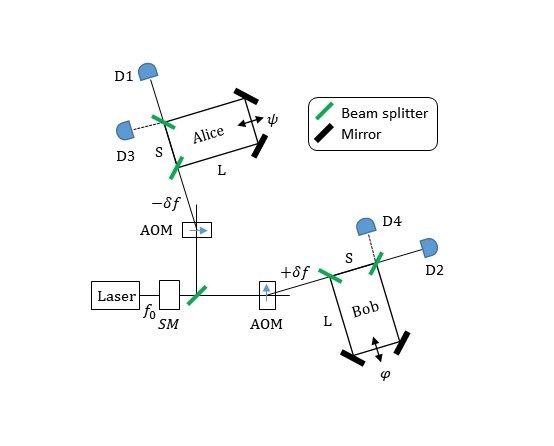

Therefore, it is possible to distinguish between two different ionization processes: one, in which the remaining electron gains additional energy and one, in which it remains in a state of minimal energy. Using a sophisticated experimental setup, it was possible to show that the duration of these two processes is not exactly the same.

“When the remaining electron jumps to an excited state, the photo ionization process is slightly faster – by about five attoseconds”, says Stefan Nagele. It is remarkable how well the experimental results agree with theoretical calculations and large-scale computer simulations carried out at the Vienna Scientific Cluster, Austria’s largest supercomputer: “The precision of the experiment is better than one attosecond. This is the most accurate time measurement of a quantum jump to date”, says Renate Pazourek.

Controlling Attoseconds

The experiment provides new insights into the physics of ultrashort time scales. Effects, which a few decades ago were still considered “instantaneous” can now be seen as temporal developments which can be calculated, measured and even controlled. This does not only help to understand the basic laws of nature, it also brings new possibilities of manipulating matter on a quantum scale.

Original publication: Attosecond Correlation Dynamics, M. Ossiander et al. Nature Physics