18 OCT 2016

WILSON DA SILVA

UNSW engineers have created a new quantum bit that remains in a stable superposition for 10 times longer than previously achieved, dramatically expanding the number of calculations that could be performed in a future silicon quantum computer.

Engineers at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) have created a new quantum bit that remains in a stable superposition for 10 times longer than previously achieved, dramatically expanding the time during which calculations could be performed in a future silicon quantum computer.

It’s another first for the diverse UNSW team that is leading the world in the ‘space race of the 21st century’.

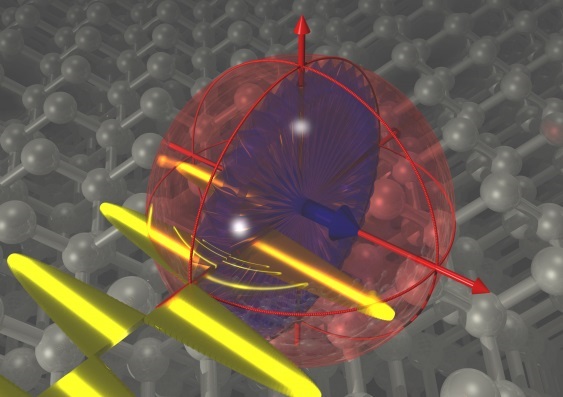

The new quantum bit, made up of the spin of a single atom in silicon and merged with an electromagnetic field – known as ‘dressed qubit’ – retains quantum information for much longer that an ‘undressed’ atom, opening up new avenues to build and operate the superpowerful quantum computers of the future.

The results are published today in the international journal, Nature Nanotechnology.

“We have created a new quantum bit where the spin of a single electron is merged together with a strong electromagnetic field,” said Arne Laucht, a Research Fellow at the School of Electrical Engineering & Telecommunications at UNSW, and lead author of the paper. “This quantum bit is more versatile and more long-lived than the electron alone, and will allow us to build more reliable quantum computers.”

Building a quantum computer has been called the ‘space race of the 21st century’ – a difficult and ambitious challenge with the potential to deliver revolutionary tools for tackling otherwise impossible calculations, such as the design of complex drugs and advanced materials, or the rapid search of massive, unsorted databases.

Its speed and power lie in the fact that quantum systems can host multiple ‘superpositions’ of different initial states, which in a computer are treated as inputs which, in turn, all get processed at the same time.

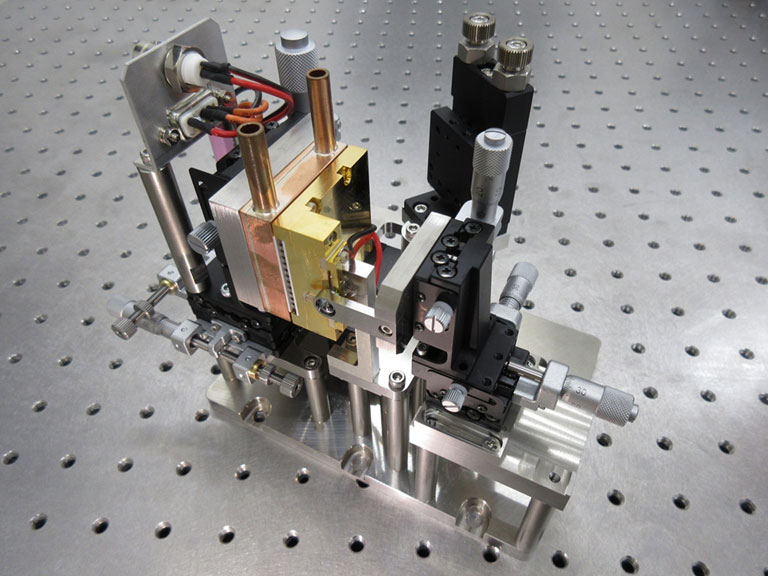

“The greatest hurdle in using quantum objects for computing is to preserve their delicate superpositions long enough to allow us to perform useful calculations,” said Andrea Morello, leader of the research team and a Program Manager in the ARC Centre for Quantum Computation & Communication Technology (CQC2T) at UNSW. “Our decade-long research program had already established the most long-lived quantum bit in the solid state, by encoding quantum information in the spin of a single phosphorus atom inside a silicon chip, placed in a static magnetic field.”

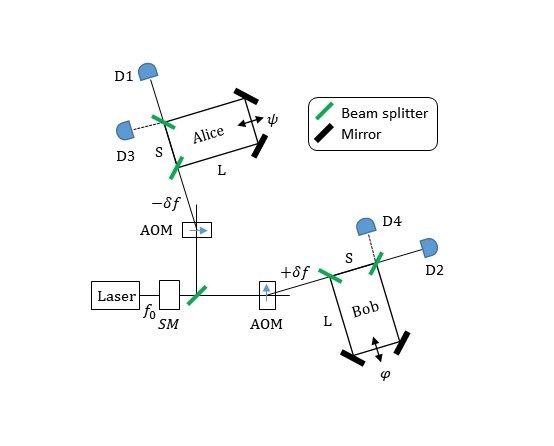

What Laucht and colleagues did was push this further: “We have now implemented a new way to encode the information: we have subjected the atom to a very strong, continuously oscillating electromagnetic field at microwave frequencies, and thus we have ‘redefined’ the quantum bit as the orientation of the spin with respect to the microwave field.”

The results are striking: since the electromagnetic field steadily oscillates at a very high frequency, any noise or disturbance at a different frequency results in a zero net effect. The researchers achieved an improvement by a factor of 10 in the time span during which a quantum superposition can be preserved.

Specifically, they measured a dephasing time of T2*=2.4 milliseconds – a result that is 10-fold better than the standard qubit, allowing many more operations to be performed within the time span during which the delicate quantum information is safely preserved.

“This new ‘dressed qubit’ can be controlled in a variety of ways that would be impractical with an ‘undressed qubit’,” added Morello. “For example, it can be controlled by simply modulating the frequency of the microwave field, just like in an FM radio. The ‘undressed qubit’ instead requires turning the amplitude of the control fields on and off, like an AM radio.

“In some sense, this is why the dressed qubit is more immune to noise: the quantum information is controlled by the frequency, which is rock-solid, whereas the amplitude can be more easily affected by external noise.”

Since the device is built upon standard silicon technology, this result paves the way to the construction of powerful and reliable quantum processors based upon the same fabrication process already used for today’s computers.

The UNSW team leads the world in developing quantum computing in silicon, and Morello’s team is part of the consortium of UNSW researchers who have struck a A$70 million deal between UNSW, the researchers, business and the Australian government to develop a prototype silicon quantum integrated circuit – the first step in building the world’s first quantum computer in silicon.

“Quantum computing is one of the great challenges of the 21st century, manipulating nature at a subatomic level and pushing into the very edge of what is possible,” said Mark Hoffman, UNSW’s Dean of Engineering. “To have a team that leads the world in this field, and consistently delivers firsts, is a testament to the extraordinary talent we have assembled in Australia at UNSW.”

A functional quantum computer would allow massive increases in speed and efficiency for certain computing tasks – even when compared with today’s fastest silicon-based ‘classical’ computers. In a number of key areas – such as searching large databases, solving complicated sets of equations, and modelling atomic systems such as biological molecules and drugs – they would far surpass today’s computers. They would also be enormously useful in the finance and healthcare industries, and for government, security and defence organisations.

Quantum computers could identify and develop new medicines by greatly accelerating the computer-aided design of pharmaceutical compounds (and minimising lengthy trial and error testing), and develop new, lighter and stronger materials spanning consumer electronics to aircraft. They would also make possible new types of computational applications and solutions that are beyond our ability to foresee.

Other researchers who contributed to the work include members of Morello’s CQC2T team at UNSW – Rachpon Kalra, Stephanie Simmons, Juan Dehollain, Juha Muhonen, Fahd Mohiyaddin and Solomon Freer; Andrew Dzurak and Fay Hudson at the Australian National Fabrication Facility; David Jamieson and Jeffrey McCallum from the CQC2T University of Melbourne team; and Kohei Itoh of Japan’s Keio University.