09 Feb 2016

Physicists at the University of Glasgow have developed a new and inexpensive way to make radially polarised white light, which could help scientific advances in astronomy and microscopy.

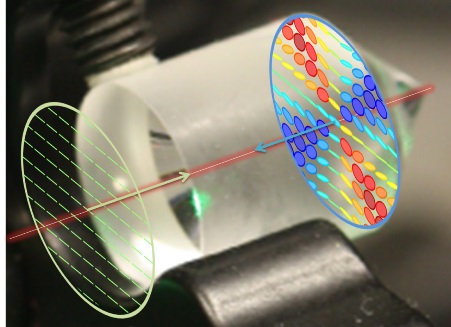

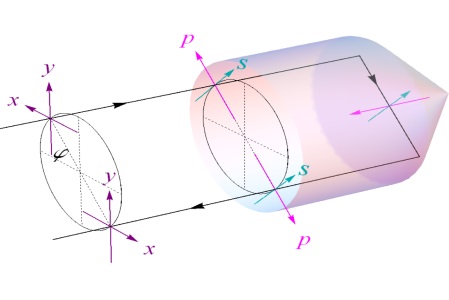

Dr Neal Radwell and Dr Sonja Franke-Arnold, from the University’s School of Physics and Astronomy, have discovered a new way of producing radially polarised beams, using broadband white light rather than single frequency beams, by reflecting the light from a glass cone.

The Glasgow-based physicists have discovered that if white light with a uniform polarisation across the whole beam is reflected back from a small glass cone, the light becomes an optical vortex, for example with polarisation always pointing to the centre. Such light can be focused on a much smaller scale than was previously thought possible.

The technological breakthrough could be useful in microscopy, as it enables scientists to record images with a much better resolution, and also in astronomy, where so-called vortex coronagraphs can be used to see faint objects from light years away that are normally obscured by near very bright stars.

Dr Neal Radwell, lead author on the report “Achromatic vector vortex beams from a glass cone”, published in Nature Communications , said: “Scientists can make these kind of beams already but we have found the first way of making radial polarisation using white light - light that contains all different colours - rather than lasers and light of a very particular frequency.

“What we have proved is not that you can focus these beams better, that has been shown before, but we have found a new way to make those beams.”

Dr Sonja Franke-Arnold, who devised the glass cone technology, said: “What is incredible to us is that such interesting physics has come from something so simple.

“We have developed a new mechanism to make radially polarised beams using white light just with a glass cone, based on the laws of reflection that have been around for more than 200 years. It’s a very simple idea and it works.

“Previously people have been using nano-fabricated devices, which are extremely expensive, but we have come up with a new mechanism to create polarisation structures which could be really useful for future applications, as it is incredibly cheap, easy to operate and robust.”

Until now scientists using radially polarised beams have tended to use single frequency light. But now scientists can use white light reflected from the glass cones, enabling them to focus on extremely small spots, far smaller than was conventionally thought to be possible, and create images with a much higher resolution.

Dr Franke-Arnold added: “The structure of these special light beams is directly linked to the geometry of the glass cones. This makes them very stable and means that we can work over large frequencies. We believe the polarisation structures we get are cleaner than any you can get elsewhere.”

As yet the commercial uses of these radially polarised beams from glass cones are still relatively unclear, but Dr Radwell explains: “It wasn’t our intent to realise commercial applications during this research, it was purely for scientific applications and inspired by scientific curiosity.

“This doesn’t allow you to do things you couldn’t do before but it does give us a new way to create these beams, which is potentially cheaper and it is broadband as it works with white light. That is why it has potential application not only in microscopy but also astronomy where researchers are interested in star ight across the whole visual spectrum.”