November 24, 2015

By Bethany Augliere

Researchers from Stanford have advanced a long-standing problem in quantum physics – how to send "entangled" particles over long distances.

Their work is described in the online edition of Nature Communications.

Scientists and engineers are interested in the practical application of this technology to make quantum networks that can send highly secure information over long distances – a capability that also makes the technology appealing to governments, banks and militaries.

Quantum entanglement is the observed phenomenon of two or more particles that are connected, even over thousands of miles. If it sounds strange, take comfort knowing that Albert Einstein described this behavior as "spooky action."

Consider, for instance, entangled electrons. Electrons spin in one of two characteristic directions, and if they are entangled, those two electrons' spins are linked. It's as if you spun a quarter in New York clockwise, an entangled second coin in Los Angeles would start to spin clockwise. And likewise, if you spun that quarter counter-clockwise, the second coin would shift its spin as well.

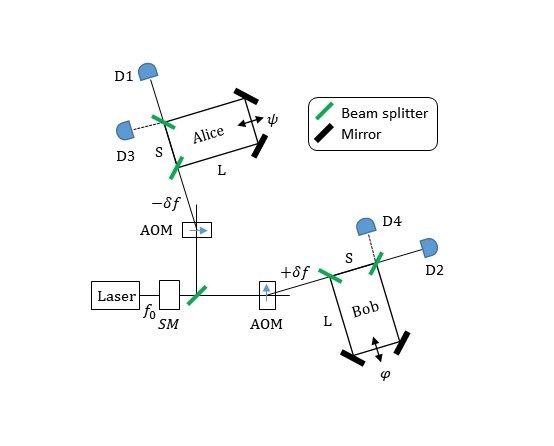

Electrons are trapped inside atoms, so entangled electrons can't talk directly at long distance. But photons – tiny particles of light – can move. Scientists can establish a necessary condition of entanglement, called quantum correlation, to correlate photons to electrons, so that the photons can act as the messengers of an electron's spin.

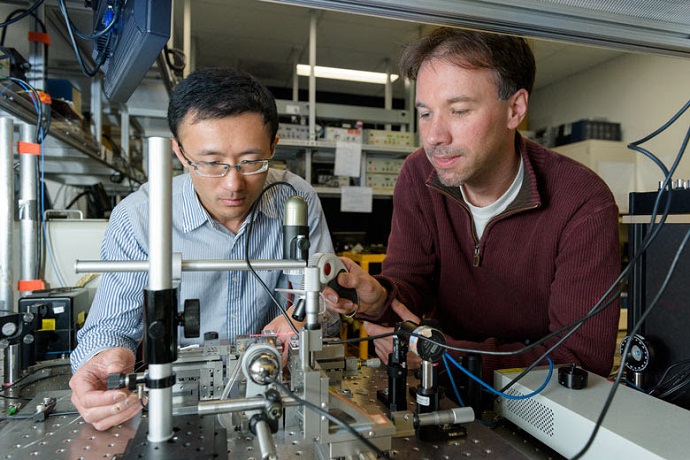

In his previous work, Stanford physicist Leo Yu has entangled photons with electrons through fiber optic cables over a distance of several feet. Now, he and a team of scientists, including Professor Emeritus Yoshihisa Yamamoto, have correlated photons with electron spin over a record distance of 1.2 miles.

"Electron spin is the basic unit of a quantum computer," Yu said. "This work can pave the way for future quantum networks that can send highly secure data around the world."

To do this, Yu and his team had to make sure that the correlation could be preserved over long distances – a key challenge given that photons have a tendency to change orientation while traveling in optical fibers.

Photons can have a vertical or horizontal orientation (known as polarization), which can be referenced as a 0 or a 1, as in digital computer programming. But if they change en route, the connection to the correlated electron is lost.

This information can be preserved in another way, Yu said. He created a time-stamp to correlate arrival time of the photon with the electron spin, which provided a sort of reference key for each photon to confirm its correlation to the source electron.

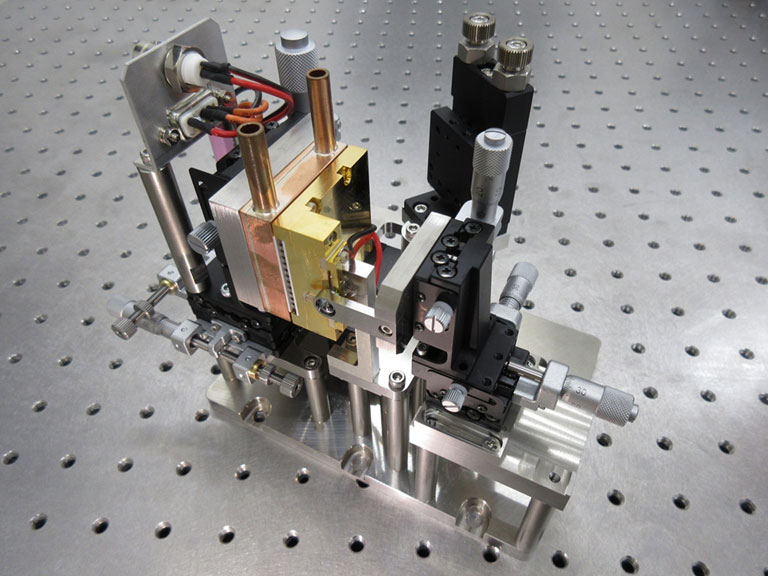

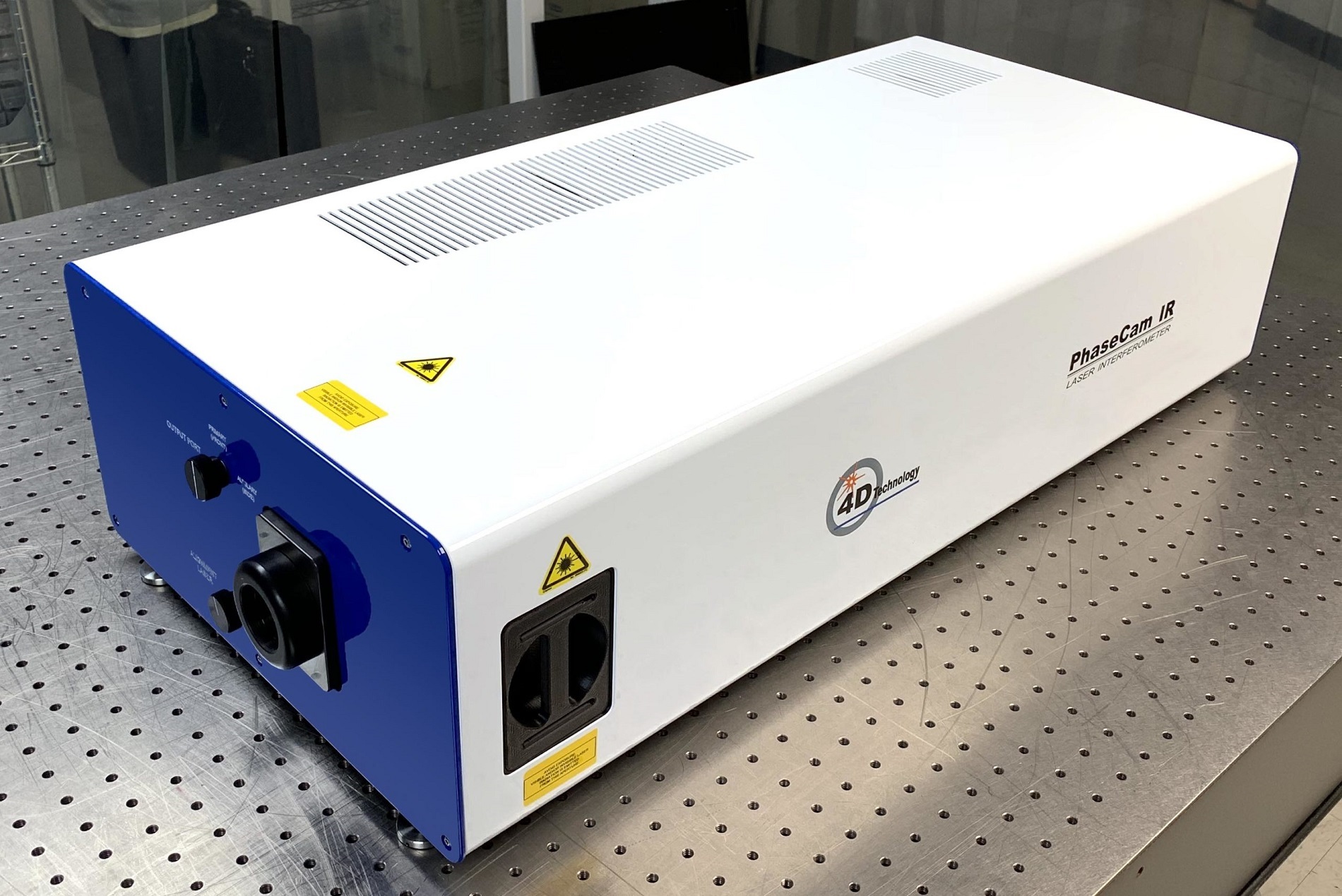

To eventually entangle two electrons that had never met over great distances, two photons, each correlated with a unique source electron, had to be sent through fiber optic cables to meet in the middle at a "beam splitter" and interact. Photons do not normally interact, just two flashlights beams passing through one another, so the researchers had to mediate this interaction called the "two-photon interference."

To ensure the two-photon interference, they had another issue to overcome. Photons from two different sources have different characteristics, like color and wavelength. If they have different wavelengths, they cannot interfere, Yu said. Before traveling along the fiber optic cable, the photons passed through a "quantum down-converter," which matched their wavelengths. The down-converter also shifted both photons to a wavelength that can travel farther within the fiber optic cables designed for telecommunications.

Quantum supercomputers promise to be exponentially faster and more powerful than traditional computers, Yu said, and can communicate with immunity to hacking or spying. With this work, the team has brought the quantum networks one step closer to reality.

The paper is published online in Nature Communications. In addition to Yu and Yamamoto, it was co-authored by Martin Fejer, Tomoyuki Horikiri, Carsten Langrock, Chandra Natarajan, Jason Pelc, Michael G. Tanner, Eisuke Abe, Sebastian Maier, Christian Schneider, Sven Höfling, Martin Kamp, and Robert H. Hadfield.

The work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the National Science Foundation, the National Institute of Information and Communications Technology, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology, and the State of Bavaria. Funding also came from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, SU2P Entrepreneurial Fellowship and Royal Society University Research Fellowship.

For more Stanford experts on physics and other topics, visit Stanford Experts.