2015/10/06

An interdisciplinary team of researchers has built the first prototype of a miniature particle accelerator that uses terahertz radiation instead of radio frequency structures. A single accelerator module is no more than 1.5 centimetres long and one millimetre thick. The terahertz technology holds the promise of miniaturising the entire set-up by at least a factor of 100, as the scientists surrounding DESY’s Franz Kärtner from the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science (CFEL) point out. They are presenting their prototype, that was set up in Kärtner's lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the U.S., in the journal Nature Communications. The authors see numerous applications for terahertz accelerators, in materials science, medicine and particle physics, as well as in building X-ray lasers. CFEL is a cooperation between DESY, the University of Hamburg and the Max Planck Society.

In the electromagnetic spectrum, terahertz radiation lies between infrared radiation and microwaves. Particle accelerators usually rely on electromagnetic radiation from the radio frequency range; DESY’s particle accelerator PETRA III, for example, uses a frequency of around 500 megahertz. The wavelength of the terahertz radiation used in this experiment is around one thousand times shorter. “The advantage is that everything else can be a thousand times smaller too,” explains Kärtner, who is also a professor at the University of Hamburg and at MIT, as well as being a member of the Hamburg Centre for Ultrafast Imaging (CUI), one of Germany’s Clusters of Excellence.

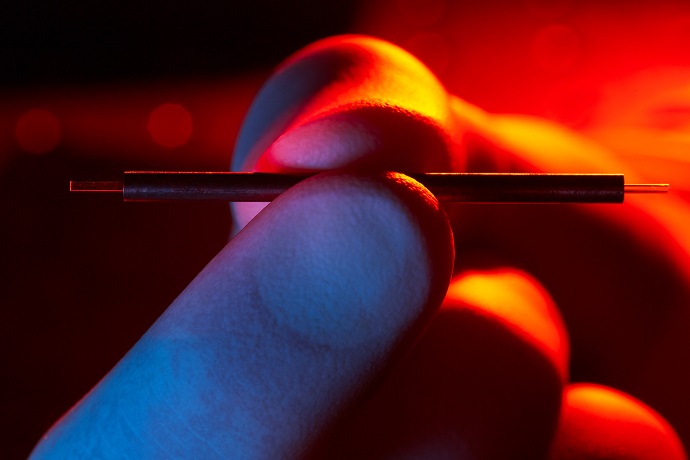

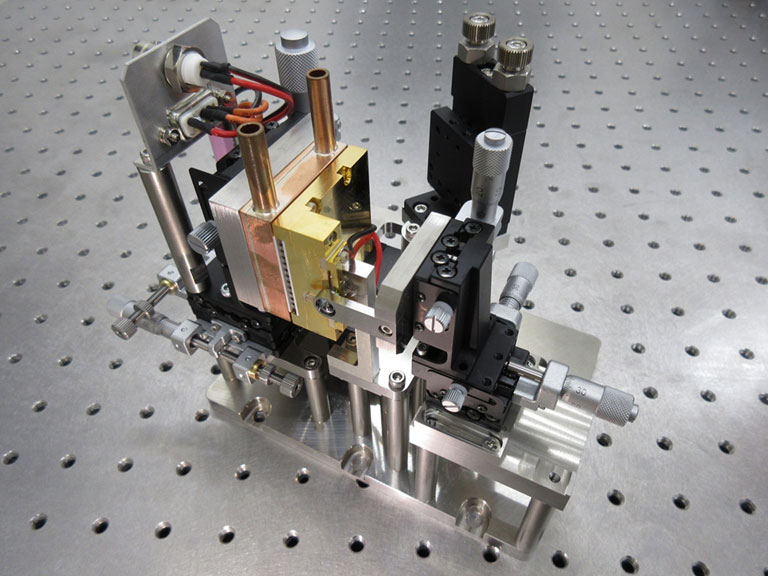

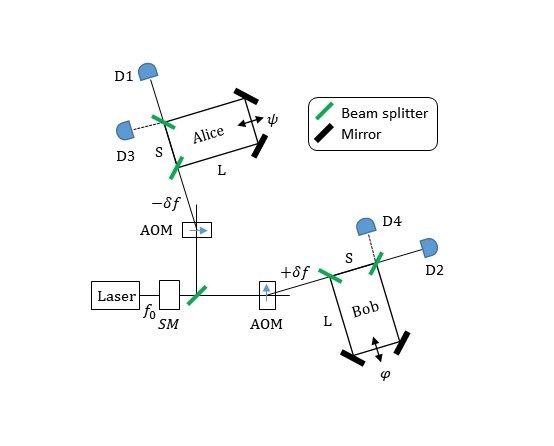

For their prototype the scientists used a special microstructured accelerator module, specifically tailored to be used with terahertz radiation. The physicists fired fast electrons into the miniature accelerator module using a type of electron gun provided by the group of CFEL Professor Dwayne Miller, Director at the Max Planck Institute for the Structure and Dynamics of Matter and also a member of CUI. The electrons were then further accelerated by the terahertz radiation fed into the module. This first prototype of a terahertz accelerator was able to increase the energy of the particles by seven kiloelectronvolts (keV).

“This is not a particularly large acceleration, but the experiment demonstrates that the principle does work in practice,” explains co-author Arya Fallahi of CFEL, who did the theoretical calculations. “The theory indicates that we should be able to achieve an accelerating gradient of up to one gigavolt per metre.” This is more than ten times what can be achieved with the best conventional accelerator modules available today. Plasma accelerator technology, which is also at an experimental stage right now, promises to produce even higher accelerations, however it also requires significantly more powerful lasers than those needed for terahertz accelerators.

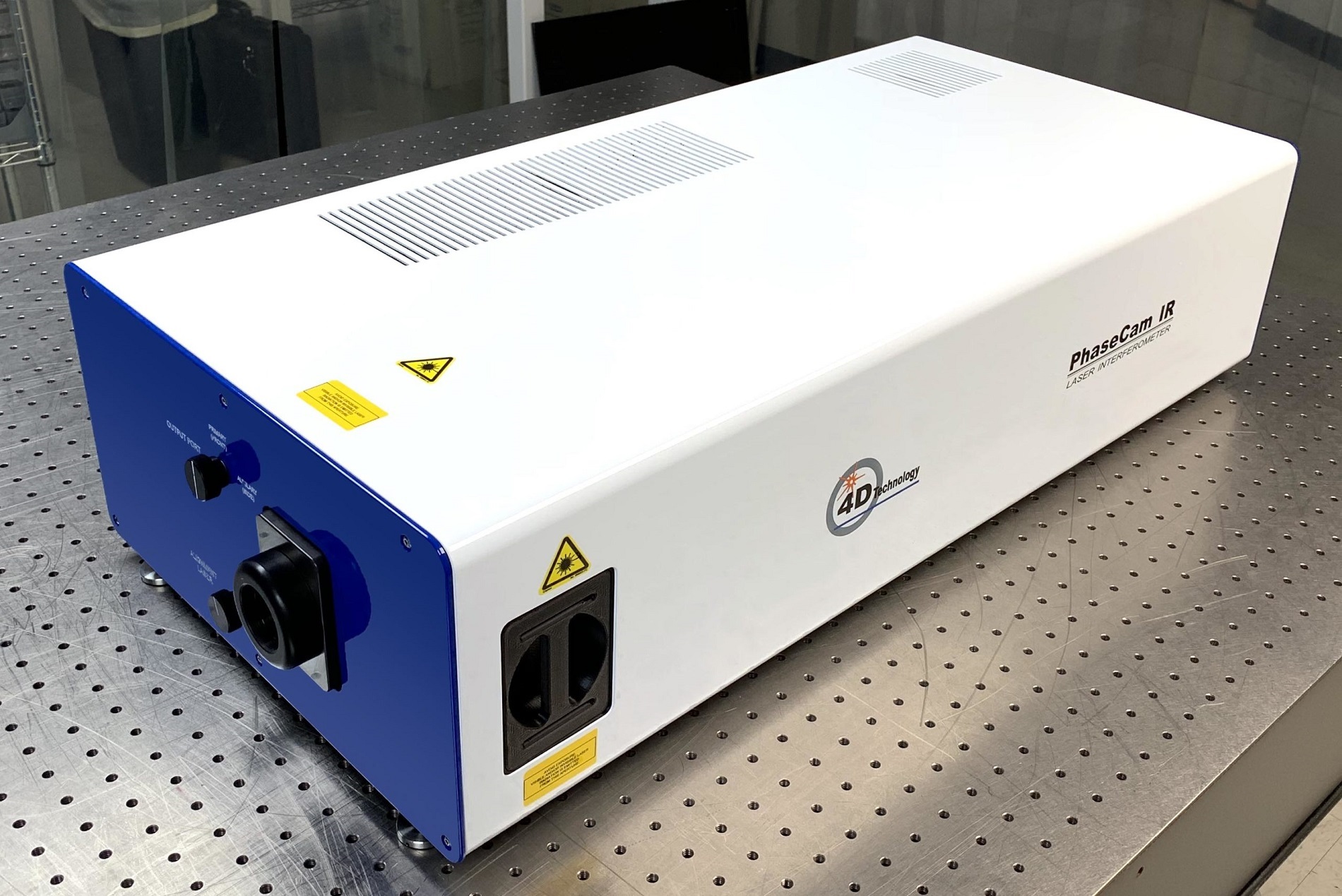

The physicists underline that terahertz technology is of great interest both with regard to future linear accelerators for use in particle physics, and as a means of building compact X-ray lasers and electron sources for use in materials research, as well as medical applications using X-rays and electron radiation. “The rapid advances we are seeing in terahertz generation with optical methods will enable the future development of terahertz accelerators for these applications,” says first author Emilio Nanni of MIT. Over the coming years, the CFEL team in Hamburg plans to build a compact, experimental free-electron X-ray laser (XFEL) on a laboratory scale using terahertz technology. This project is supported by a Synergy Grant of the European Research Council.

So-called free-electron lasers (FELs) generate flashes of laser light by sending high-speed electrons from a particle accelerator down an undulating path, whereby these emit light every time they are deflected. This is the same principle that will be used by the X-ray laser European XFEL, which is currently being built by an international consortium, reaching from the DESY Campus in Hamburg to the neighbouring town of Schenefeld, in Schleswig-Holstein. The entire facility will be more than three kilometres long and will be the best and most modern of its kind after completion.

The experimental XFEL using terahertz technology is expected to be less than a metre long. “We expect this sort of device to produce much shorter X-ray pulses lasting less than a femtosecond”, says Kärtner. Because the pulses are so short, they reach a comparable peak brightness to those produced by larger facilities, even if there is significant less light in each pulse. “With these very short pulses we are hoping to gain new insights into extremely rapid chemical processes, such as those involved in photosynthesis.”

Developing a detailed understanding of photosynthesis would open up the possibility of implementing this efficient process artificially and thus tapping into increasingly efficient solar energy conversion and new pathways for CO2 reduction. Beyond this, researchers are interested in numerous other chemical reactions. As Kärtner points out, “photosynthesis is just one example of many possible catalytic processes we would like to investigate.” The compact XFEL can be potentially also used to seed pulses in large scale facilities to enhance the quality of their pulses. Also, certain medical imaging techniques could benefit from the enhanced characteristics of the novel X-ray source.

Reference:

„Terahertz-driven linear electron acceleration“; Emilio A. Nanni, Wenqian R. Huang, Kyung-Han Hong, Koustuban Ravi, Arya Fallahi, Gustavo Moriena, R. J. Dwayne Miller & Franz X. Kärtner; Nature Communications, 2015; DOI: 10.1038/NCOMMS9486