June 15, 2015

Einstein’s theory of time and space will celebrate its 100th anniversary this year. Even today it captures the imagination of scientists. In an international collaboration, researchers from the Universities of Vienna (Časlav Brukner), Harvard (Igor Pikovski) and Queensland have now discovered that this world-famous theory can explain yet another puzzling phenomenon: the transition from quantum behavior to our classical, everyday world. Their results are published in the journal "Nature Physics".

In 1915 Albert Einstein formulated the theory of general relativity which fundamentally changed our understanding of gravity. He explained gravity as the manifestation of the curvature of space and time. Einstein’s theory predicts that the flow of time is altered by mass. This effect, known as "gravitational time dilation", causes time to be slowed down near a massive object. It affects everything and everybody; in fact, people working on the ground floor will age slower than their colleagues a floor above, by about 10 nanoseconds in one year. This tiny effect has actually been confirmed in many experiments with very precise clocks. Now, a team of researchers from the University of Vienna, Harvard University and the University of Queensland have discovered that the slowing down of time can explain another perplexing phenomenon: the transition from quantum behavior to our classical, everyday world.

How gravity suppresses quantum behavior

Quantum theory, the other major discovery in physics in the early 20th century, predicts that the fundamental building blocks of nature show fascinating and mind-boggling behavior. Extrapolated to the scales of our everyday life quantum theory leads to situations such as the famous example of Schroedinger’s cat: the cat is neither dead nor alive, but in a so-called quantum superposition of both. Yet such a behavior has only been confirmed experimentally with small particles and has never been observed with real-world cats. Therefore, scientists conclude that something must cause the suppression of quantum phenomena on larger, everyday scales. Typically this happens because of interaction with other surrounding particles.

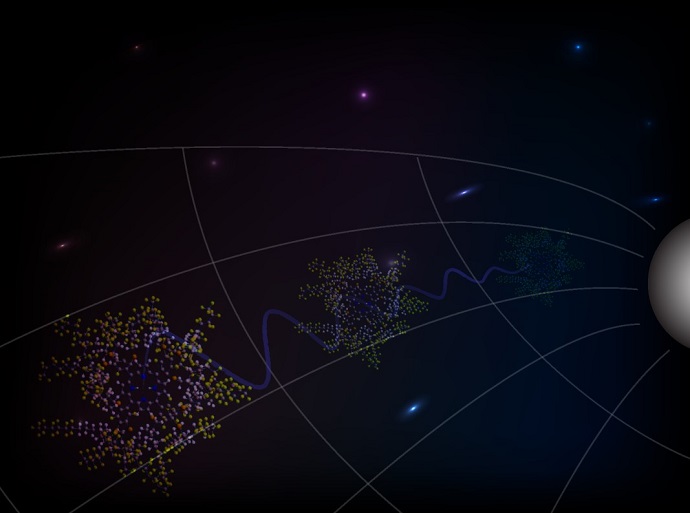

The research team, headed by Časlav Brukner from the University of Vienna and the Institute of Quantum Optics and Quantum Information, found that time dilation also plays a major role in the demise of quantum effects. They calculated that once the small building blocks form larger, composite objects – such as molecules and eventually larger structures like microbes or dust particles –, the time dilation on Earth can cause a suppression of their quantum behavior. The tiny building blocks jitter ever so slightly, even as they form larger objects. And this jitter is affected by time dilation: it is slowed down on the ground and speeds up at higher altitudes. The researchers have shown that this effect destroys the quantum superposition and, thus, forces larger objects to behave as we expect in everyday life.

Paving the way for the next generation of quantum experiments

"It is quite surprising that gravity can play any role in quantum mechanics", says Igor Pikovski, who is the lead author of the publication and is now working at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics: "Gravity is usually studied on astronomical scales, but it seems that it also alters the quantum nature of the smallest particles on Earth". "It remains to be seen what the results imply on cosmological scales, where gravity can be much stronger", adds Časlav Brukner. The results of Pikovski and his co-workers reveal how larger particles lose their quantum behavior due to their own composition, if one takes time dilation into account. This prediction should be observable in experiments in the near future, which could shed some light on the fascinating interplay between the two great theories of the 20th century, quantum theory and general relativity.

Publication in "Nature Physics":

"Universal decoherence due to gravitational time dilation". I. Pikovski, M. Zych, F. Costa, Č. Brukner.

Nature Physics (2015)

DOI:10.1038/nphys3366

Einstein saves the quantum cat

Relativity theory also applicable in other research areas

Illustration of a molecule in the presence of gravitational time dilation. The molecule is in a quantum superposition of being in several places at the same time, but time dilation destroys this quantum phenomenon (Copyright: Igor Pikovski, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysic).