July 31, 2014

Graphene, an ultrathin form of carbon with exceptional electrical, optical, and mechanical properties, has become a focus of research on a variety of potential uses. Now researchers at MIT have found a way to control how the material conducts electricity by using extremely short light pulses, which could enable its use as a broadband light detector.

The new findings are published in the journal Physical Review Letters, in a paper by graduate student Alex Frenzel, Nuh Gedik, and three others.

The researchers found that by controlling the concentration of electrons in a graphene sheet, they could change the way the material responds to a short but intense light pulse. If the graphene sheet starts out with low electron concentration, the pulse increases the material’s electrical conductivity. This behavior is similar to that of traditional semiconductors, such as silicon and germanium.

But if the graphene starts out with high electron concentration, the pulse decreases its conductivity — the same way that a metal usually behaves. Therefore, by modulating graphene’s electron concentration, the researchers found that they could effectively alter graphene’s photoconductive properties from semiconductorlike to metallike.

The finding also explains the photoresponse of graphene reported previously by different research groups, which studied graphene samples with differing concentration of electrons. “We were able to tune the number of electrons in graphene, and get either response,” Frenzel says.

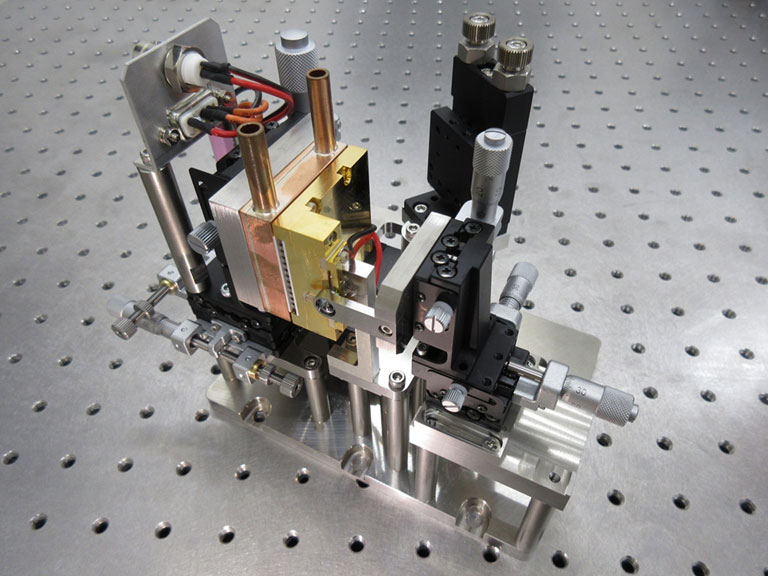

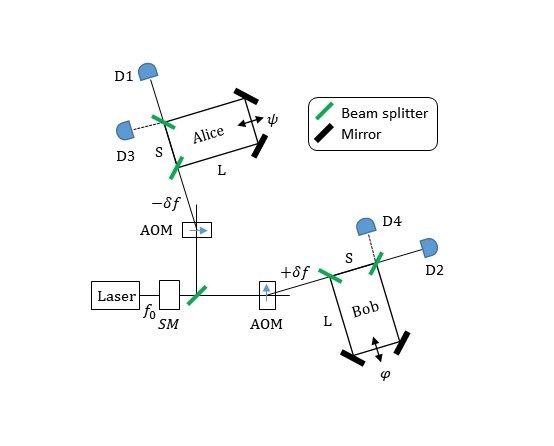

To perform this study, the team deposited graphene on top of an insulating layer with a thin metallic film beneath it; by applying a voltage between graphene and the bottom electrode, the electron concentration of graphene could be tuned. The researchers then illuminated graphene with a strong light pulse and measured the change of electrical conduction by assessing the transmission of a second, low-frequency light pulse.

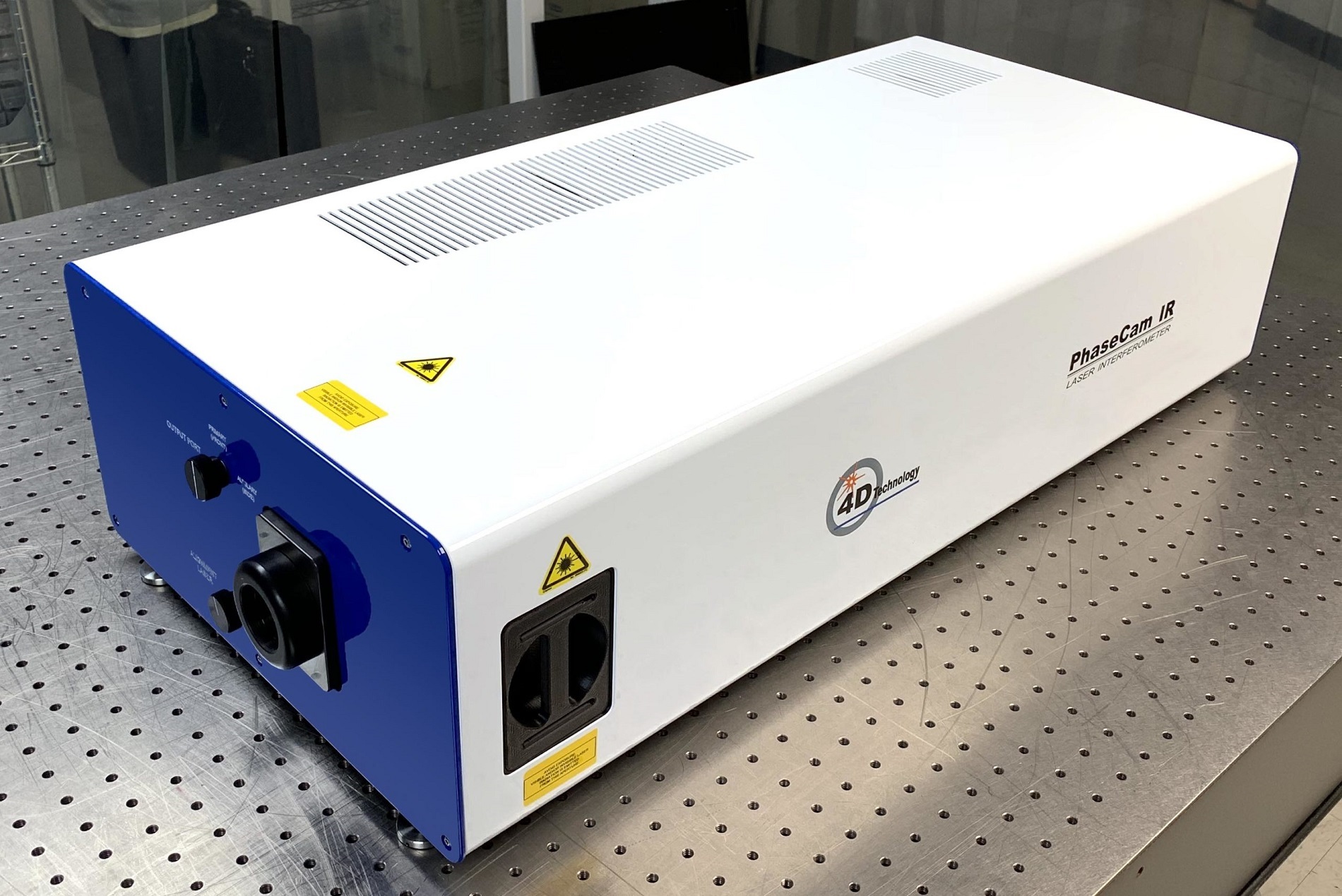

In this case, the laser performs dual functions. “We use two different light pulses: one to modify the material, and one to measure the electrical conduction,” Gedik says, adding that the pulses used to measure the conduction are much lower frequency than the pulses used to modify the material behavior. To accomplish this, the researchers developed a device that was transparent, Frenzel explains, to allow laser pulses to pass through it.

This all-optical method avoids the need for adding extra electrical contacts to the graphene. Gedik, the Lawrence C. and Sarah W. Biedenharn Associate Professor of Physics, says the measurement method that Frenzel implemented is a “cool technique. Normally, to measure conductivity you have to put leads on it,” he says. This approach, by contrast, “has no contact at all.”

Additionally, the short light pulses allow the researchers to change and reveal graphene’s electrical response in only a trillionth of a second.

In a surprising finding, the team discovered that part of the conductivity reduction at high electron concentration stems from a unique characteristic of graphene: Its electrons travel at a constant speed, similar to photons, which causes the conductivity to decrease when the electron temperature increases under the illumination of the laser pulse. “Our experiment reveals that the cause of photoconductivity in graphene is very different from that in a normal metal or semiconductor,” Frenzel says.

The researchers say the work could aid the development of new light detectors with ultrafast response times and high sensitivity across a wide range of light frequencies, from the infrared to ultraviolet. While the material is sensitive to a broad range of frequencies, the actual percentage of light absorbed is small. Practical application of such a detector would therefore require increasing absorption efficiency, such as by using multiple layers of graphene, Gedik says.

Isabella Gierz, a professor at the Max Planck Institute for the Structure and Dynamics of Matter in Hamburg, Germany, who was not involved in this research, says, “The work is interesting because it presents a systematic study of the doping dependence of the low-energy dynamics, which has not received much attention so far.” She says the new research “certainly helps to reconcile previous apparently contradicting results,” and adds that these findings represent “a solid experiment, analysis, and interpretation.”

The research team also included Jing Kong, the ITT Career Development Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering at MIT, who provided the graphene samples used for the experiments; physics postdoc Chun Hung Lui; and Yong Cheol Shin, a graduate student in materials science and engineering. The work received support from the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation.