August 9, 2013

By Angela Herring

Hold a magnifying glass over the driveway on a sunny day and it will focus sunlight into a single beam. Hold a prism in front of the window and the light will spread out into a perfect rainbow. Lenses like these have been used for thousands of years, including, most recently, for sophisticated optical devices.

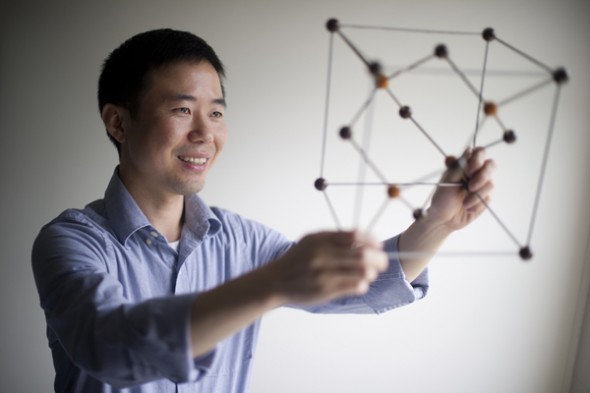

Until now, all lenses have shared one big limitation: It’s impossible to focus light into a beam that’s smaller than half of the light’s wavelength, said assistant professor Yongmin Liu. It would be like trying to compress golf balls into a cylinder whose diameter was smaller than the balls themselves.

This so-called “diffraction limit” has thus far prevented technologies based on photons (instead of electrons) from competing with the small sizes achieved in electronic devices—like the tiny chips powering our palm-sized cell phones.

But an emerging field called plasmonics has turned this age-old truth on its head and could revolutionize high-tech devices from super-resolution optical microscopes, to ultra-bright LED displays, to high-speed computers, said Liu. Researchers are now able to focus light into a beam as small as 10 nanometers in diameter, a small fraction of the shortest wavelength in the visible spectrum.

The trick is to get the photons and electrons to behave as one. When you do this, the resulting particle emerges with the features and advantages of each. The unique combination could lead to the creation of an “ultra-small, ultra-fast, and energy efficient device,” said Liu, who holds joint appointments in the Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering and the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

Yet, despite this exciting advancement, Liu wasn’t satisfied. The current devices in this field are all based on solid materials. In a liquid environment, Liu conjectured, he would have more control on the devices’ properties. Perhaps he could develop devices that are not only small and fast, but also reconfigurable and multifunctional.

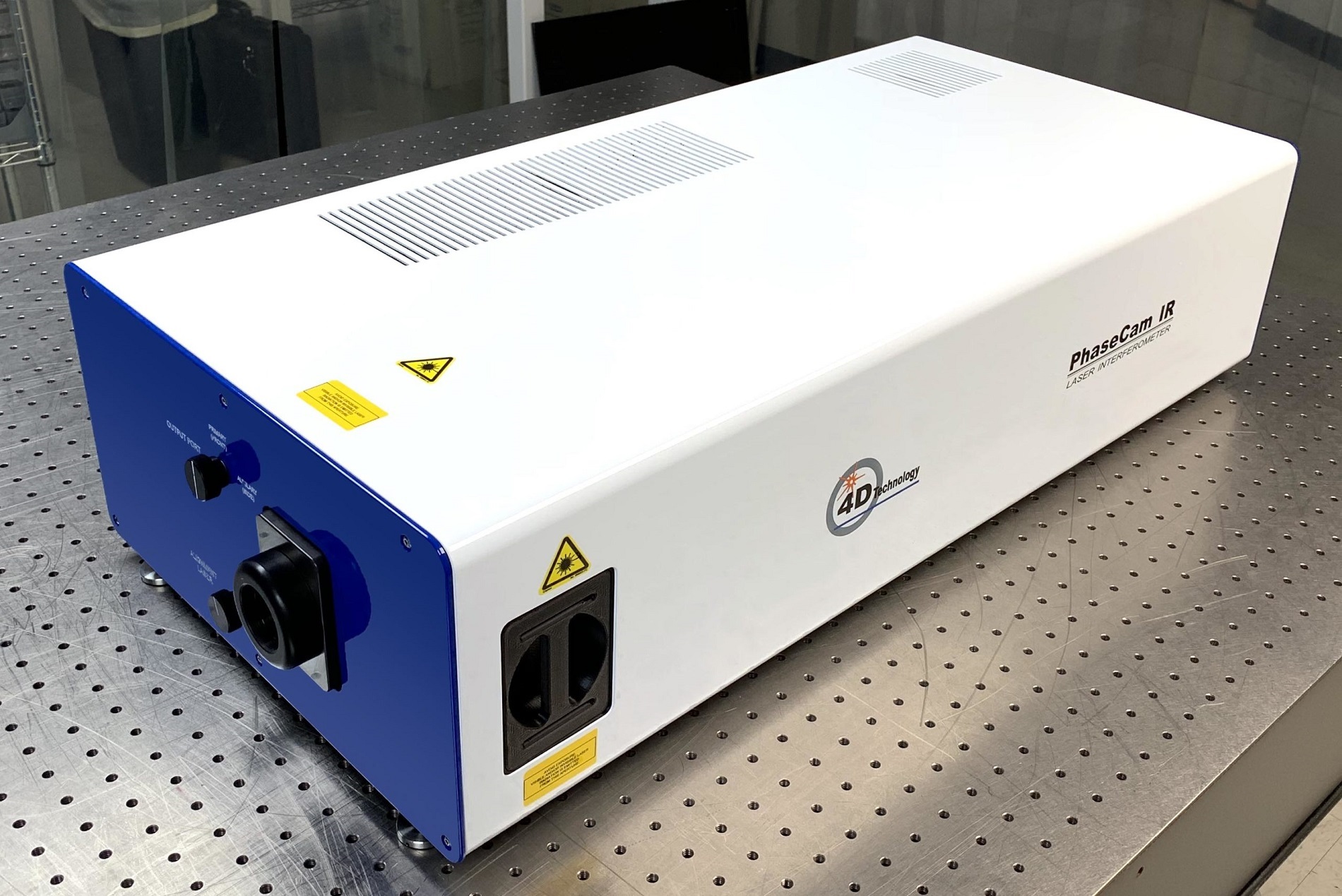

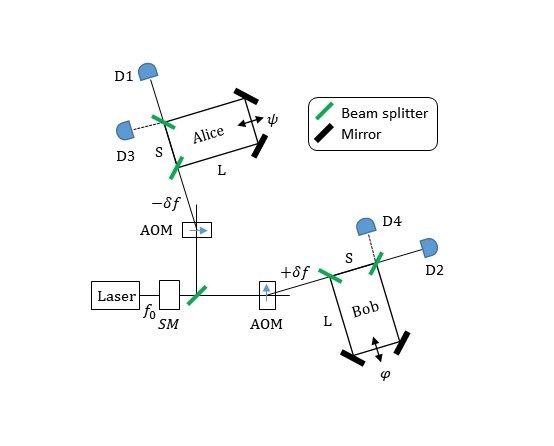

Liu teamed up with Tony Jun Huang, an engineering professor at Pennsylvania State University who studies optofluidics, Penn State postdoctoral fellow Chenglong Zhao and graduate student Yanhui Zhao, and Nicholas Fang, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at M.I.T. Combining their expertise, the team created the world’s first “plasmofluidic lens,” which uses water bubbles to manipulate light instead of glass or polymers. This work was published Friday in the journal Nature Communications.

Just as with glass blowing, the bubbles are created from heat—only instead of coming from a burning metal rod six feet long, this heat comes from a tiny laser beam just a few micrometers wide. And just like soap bubbles in a bathtub, the microscopic water bubbles are free to move around a surface, such as a piece of gold film.

The researchers can use the laser beam to change the size, shape, and location of the bubbles, allowing them to control exactly how and where the light is directed. With one lens, they can simultaneously focus, scatter, and align the photons from a single beam of light.

Combining the size capabilities of electronics with the speed capabilities of optics, and the versatility of the fluid environment, said Liu, the approach provides fertile ground for a host of new technologies we haven’t yet imagined. In particular, it could open up an entirely new class of biomedical diagnostic tools.