November 21, 2013

By Charlotte Hsu

BUFFALO, N.Y. — It’s not X-ray vision, but you could call it infrared vision.

A University at Buffalo-led research team has developed a technique for “seeing through” a stack of graphene sheets to identify and describe the electronic properties of each individual sheet — even when the sheets are covering each other up.

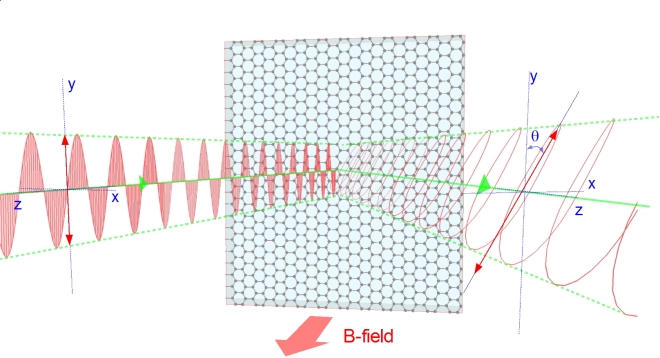

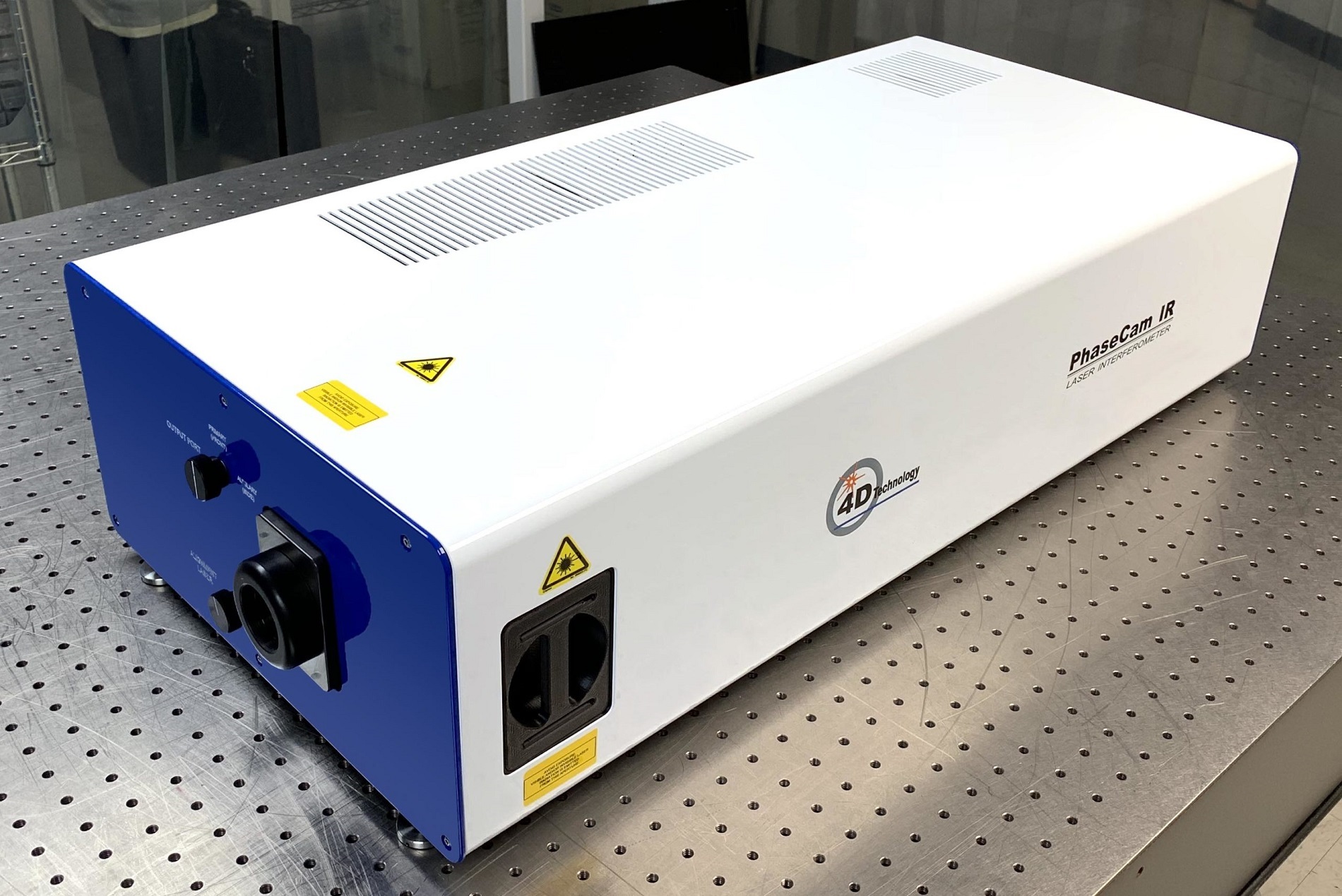

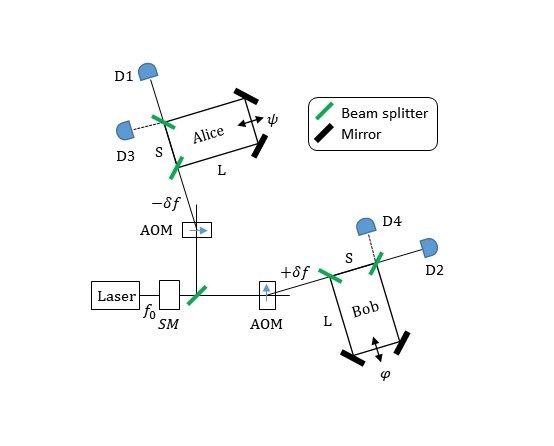

The method involves shooting a beam of infrared light at the stack, and measuring how the light wave's direction of oscillation changes as it bounces off the layers within.

To explain further: When a magnetic field is applied and increased, different types of graphene alter the direction of oscillation, or polarization, in different ways. A graphene layer stacked neatly on top of another will have a different effect on polarization than a graphene layer that is messily stacked.

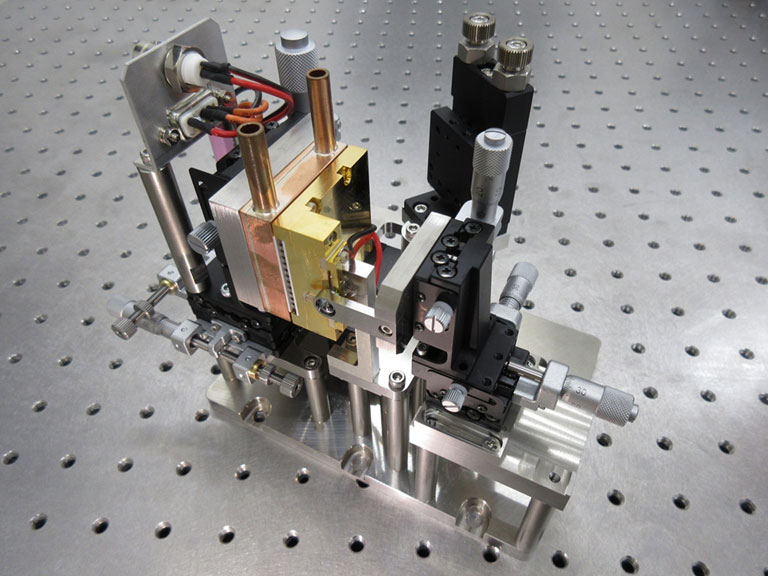

“By measuring the polarization of reflected light from graphene in a magnetic field and using new analysis techniques, we have developed an ultrasensitive fingerprinting tool that is capable of identifying and characterizing different graphene multilayers,” said John Cerne, PhD, UB associate professor of physics, who led the project.

The technique allows the researchers to examine dozens of individual layers within a stack.

Graphene, a nanomaterial that consists of a single layer of carbon atoms, has generated huge interest due to its remarkable fundamental properties and technological applications. It’s lightweight but also one of the world’s strongest materials. So incredible are its characteristics that it garnered a Nobel Prize in Physics in 2010 for two scientists who pioneered its study.

Cerne’s new research looks at graphene’s electronic properties, which change as sheets of the material are stacked on top of one another. The findings appeared Nov. 5 in Scientific Reports, an online, open-access journal produced by the publishers of Nature.

Cerne’s collaborators included colleagues from UB and the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory.

So, why don’t all graphene layers affect the polarization of light the same way?

Cerne says the answer lies in the fact that different layers absorb and emit light in different ways.

The study showed that absorption and emission patterns change when a magnetic field is applied, which means that scientists can turn the polarization of light on and off either by applying a magnetic field to graphene layers or, more quickly, by applying a voltage that sends electrons flowing through the graphene.

“Applying a voltage would allow for fast modulation, which opens up the possibility for new optical devices using graphene for communications, imaging and signal processing,” said first author Chase T. Ellis, a former graduate research assistant at UB and current postdoctoral fellow at the Naval Research Laboratory.