By Manny Morone

Cambridge, Mass. – August 20, 2013 – Applied physicists at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) have demonstrated that they can change the intensity, phase, and polarization of light rays using a hologram-like design decorated with nanoscale structures.

As a proof of principle, the researchers have used it to create an unusual state of light called a radially polarized beam, which—because it can be focused very tightly—is important for applications like high-resolution lithography and for trapping and manipulating tiny particles like viruses.

This is the first time a single, simple device has been designed to control these three major properties of light at once. (Phase describes how two waves interfere to either strengthen or cancel each other, depending on how their crests and troughs overlap; polarization describes the direction of light vibrations; and the intensity is the brightness.)

“Our lab works on using nanotechnology to play with light,” says Patrice Genevet, a research associate at Harvard SEAS and co-lead author of a paper published this month in Nano Letters. “In this research, we’ve used holography in a novel way, incorporating cutting-edge nanotechnology in the form of subwavelength structures at a scale of just tens of nanometers.” One nanometer equals one billionth of a meter.

Genevet works in the laboratory of Federico Capasso, Robert L. Wallace Professor of Applied Physics and Vinton Hayes Senior Research Fellow in Electrical Engineering at Harvard SEAS. Capasso’s research group in recent years has focused on nanophotonics—the manipulation of light at the nanometer scale—with the goal of creating new light beams and special effects that arise from the interaction of light with nanostructured materials.

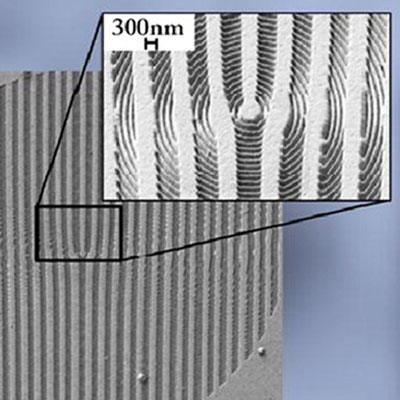

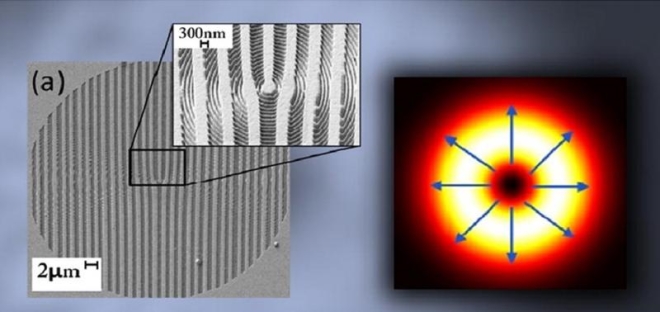

Left: holographic component fabricated by ion milling with a focused ion beam a 150-nanometer-thick gold film deposited on a glass substrate. A laser beam is partially transformed into a radially polarized beam as it traverses the device. The wide grooves create the donut-shaped intensity profile, known as a vortex, while the sub-wavelength nanometer grooves in the inset determine locally the radial polarization, which is perpendicular to the grooves. Right: The computed characteristic beam cross-section; the blue arrows indicate the radial polarization. (Image courtesy of Federico Capasso.)

Using these novel nanostructured holograms, the Harvard researchers have converted conventional, circularly polarized laser light into radially polarized beams at wavelengths spanning the technologically important visible and near-infrared light spectrum.

“When light is radially polarized, its electromagnetic vibrations oscillate inward and outward from the center of the beam like the spokes of a wheel,” explains Capasso. “This unusual beam manifests itself as a very intense ring of light with a dark spot in the center.”

“It is noteworthy,” Capasso points out, “that the same nanostructured holographic plate can be used to create radially polarized light at so many different wavelengths. Radially polarized light can be focused much more tightly than conventionally polarized light, thus enabling many potential applications in microscopy and nanoparticle manipulation.”

The new device resembles a normal hologram grating with an additional, nanostructured pattern carved into it. Visible light, which has a wavelength in the hundreds of nanometers, interacts differently with apertures textured on the ‘nano’ scale than with those on the scale of micrometers or larger. By exploiting these behaviors, the modular interface can bend incoming light to adjust its intensity, phase, and polarization.

Holograms, beyond being a staple of science-fiction universes, find many applications in security, like the holographic panels on credit cards and passports, and new digital hologram-based data-storage methods are currently being designed to potentially replace current systems. Achieving fine-tuned control of light is critical to advancing these technologies.

“Now, you can control everything you need with just a single interface,” says Genevet, pointing out that the polarization effect the new interface has on light could formerly only be achieved by a cascade of several different optical elements. “We’re gaining a big advantage in terms of saving space.”

The demonstration of this nanostructured hologram has become possible only recently with the development of more powerful software and higher resolution nanofabrication technologies.

The underlying design is more complex than a simple superposition of nanostructures onto the hologram. The phase and polarization of light closely interact, so the structures must be designed with both outcomes in mind, using modern computational tools.

Further research will aim to make more complex polarized holograms and to optimize the output efficiency of the device.

Genevet’s and Capasso’s collaborators included co-lead author Jiao Lin, a former SEAS postdoctoral fellow who is now at the Singapore Institute of Manufacturing Technology; Mikhail Kats, a graduate student at Harvard SEAS; and Nicholas Antoniou, principal focused ion beam engineer at the Center for Nanoscale Systems at Harvard University.

This research was supported in part by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9550-12-1-0289); the National Science Foundation (NSF), through a Graduate Research Fellowship; and the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) in Singapore. Device fabrication was carried out at the Center for Nanoscale Systems at Harvard University, which is a member of the NSF-supported National Nanotechnology Infrastructure Network (ECS-0335765).