15 November 2016

Researchers from TU Delft and Graphenea in Spain have found a new way to create mechanical pixels using tiny, balloon-like structures. These pixels, which do not emit light themselves but are visible in sunlight, could lead to energy-efficient colour displays that can be used in devices such as e-books and smart watches.

The pixels in question are circular indents of about 13 micrometers wide, cut into silicon and covered by a double layer of graphene that is two atoms thick. These graphene membranes enclose air inside the cavities. Santiago Cartamil-Bueno, a PhD student at TU Delft, carried out the experimental work and was the first to observe a change in color in the small devices. “At first, I was disappointed since I was researching these devices to see if they might have a function as sensors”, Cartamil-Bueno recalled. “Seeing the colours under a microscope, I realized that the devices were not homogeneous, which is bad if you are trying to create a sensor.” Besides being disappointed, the researchers were also puzzled. What was causing these colour differences?

Changing colours

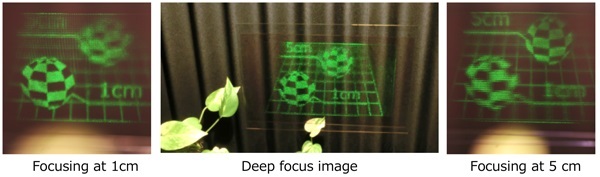

The researchers then observed the membrane-covered cavities for a longer period of time, and saw that their colours were not constant. Dr. Samer Houri, a researcher at TU Delft, led the exciting work. “We observed Newton rings and noticed their color changing over time,” he said. It quickly became clear that the devices were behaving like tiny balloons. In some of them, pressure differences between the cavity and the outside atmosphere caused the graphene membrane to be pressed downwards, towards the bottom of the cavity. By having more pressure inside than outside, the membrane was pushed upwards.

The color change effect, the researchers now realized, arose from interference between light waves reflected from the bottom of the cavity and the membrane on top. These reflected waves will interfere constructively or destructively depending on the position of the membrane, either adding up or cancelling out different parts of the spectrum of white light. When the membranes are closer to the silicon, they appear blue. When the membranes are pushed upwards, away from the silicon, they appear red.

Controlling the effect

By applying a pressure difference across the graphene membranes, the perceived color of the graphene can be shifted continuously. This effect can be exploited in order to create colored pixels in e-readers and other low-powered screens. The researchers are now working to control the color of the membranes electrically.

Santiago Cartamil-Bueno is convinced of the impact of his work “These devices provide a means to implement display technology based on interferometric modulation”, he said. Interferometric modulation, or IMOD, is employed in displays that have low power consumption requirements, such as smartwatches and ebooks.

Currently, IMOD displays are composed of mechanical pixels made of silicon materials. “By using graphene instead, with its extraordinary mechanical properties,” Santiago continues, “an IMOD could drastically improve the device performance –power consumption, pixel response time, failure rates, etc.– while enabling electrical integration and even flexible devices”. The researchers hope to have a screen prototype for the Mobile World Conference 2017 in Barcelona.

The research paper was co-authored by Santiago J. Cartamil-Bueno, Prof. Peter G. Steeneken, Prof. Herre van der Zant and Dr. Samer Houri from TU Delft and researcher Alba Centeno and scientific director Amaia Zurutuza from Graphenea.

The research was a collaborative effort from researchers at TU Delft, Netherlands, and Graphenea, Spain, as part of the Graphene Flagship. The study has recently been published in the journal Nano Letters.