August 28, 2014

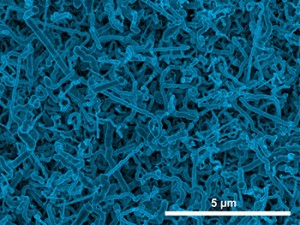

Researchers at Missouri University of Science and Technology have developed what they call “a simple, one-step method” to grow nanowires of germanium from an aqueous solution. Their process could make it more feasible to use germanium in lithium-ion batteries.

The Missouri S&T researchers describe their method in “Electrodeposited Germanium Nanowires,” a paper published today (Thursday, Aug. 28, 2014) on the website of the journal ACS Nano. Their one-step approach could lead to a simpler, less expensive way to grow germanium nanowires.

As a semiconductor material, germanium is superior to silicon, says Dr. Jay A. Switzer, the Donald L. Castleman/Foundation for Chemical Research Professor of Discover at Missouri S&T. Germanium was even used in the first transistors. But it is more expensive to process for widespread use in batteries, solar cells, transistors and other applications, says Switzer, who is the lead researcher on the project.

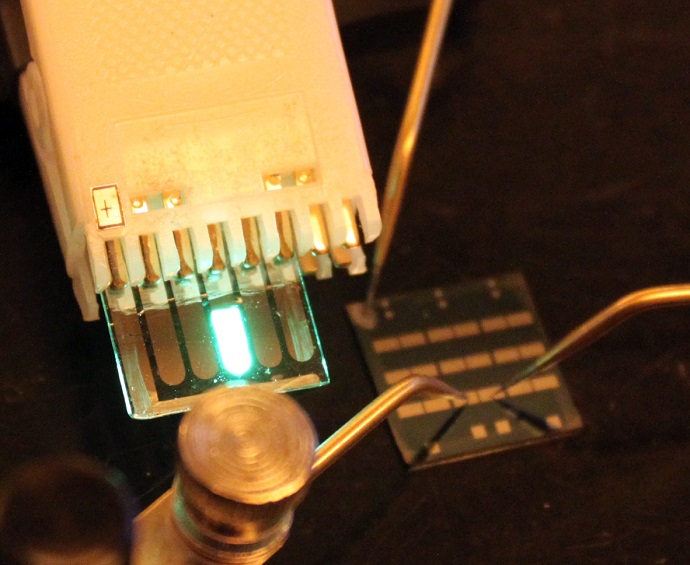

Switzer and his team have had success growing other materials at the nanometer scale through electrodeposition – a process that Switzer likens to “growing rock candy crystals on a string.” For example, in a 2009 Chemistry of Materials paper, Switzer and his team reported that they had grown zinc oxide “nanospears” – each hundreds of times smaller than the width of a human hair – on a single-crystal silicon wafer placed in a beaker filled with an alkaline solution saturated with zinc ions.

But growing germanium at the nano level is not so simple. In fact, electrodeposition in an aqueous solution such as that used to grow the zinc oxide nanospears “is thermodynamically not feasible,” Switzer and his team explain in their ACS Nano paper, “Electrodeposited Germanium Nanowires.”

So the Missouri S&T researchers took a different approach. They modified an electrodeposition process found to produce germanium nanowires using liquid metal electrodes. That process, developed by University of Michigan researchers led by Dr. Stephen Maldonado and known as the electrochemical liquid-liquid-solid process (ec-LLS), involves the use of a metallic liquid that performs two functions: It acts as an electrode to cause the electrodeposition as well as a solvent to recrystallize nanoparticles.

Switzer and his team applied the ec-LLS process by electrochemically reducing indium-tin oxide (ITO) to produce indium nanoparticles in a solution containing germanium dioxide, or Ge(IV). “The indium nanoparticle in contact with the ITO acts as the electrode for the reduction of Ge(IV) and also dissolves the reduced Ge into the particle,” the Missouri S&T team reports in the ACS Nanopaper. The germanium then “starts to crystallize out of the nanoparticle allowing the growth of the nanowire.”

The Missouri S&T researchers tested the effect of temperature for electrodeposition by growing the germanium nanowires at room temperature and at 95 degrees Celsius (203 degrees Fahrenheit). They found no significant difference in the quality of the nanowires, although the nanowires grown at room temperature had smaller diameters. Switzer believes that the ability to produce the nanowires at room temperature through this one-step process could lead to a less expensive way to produce the material.

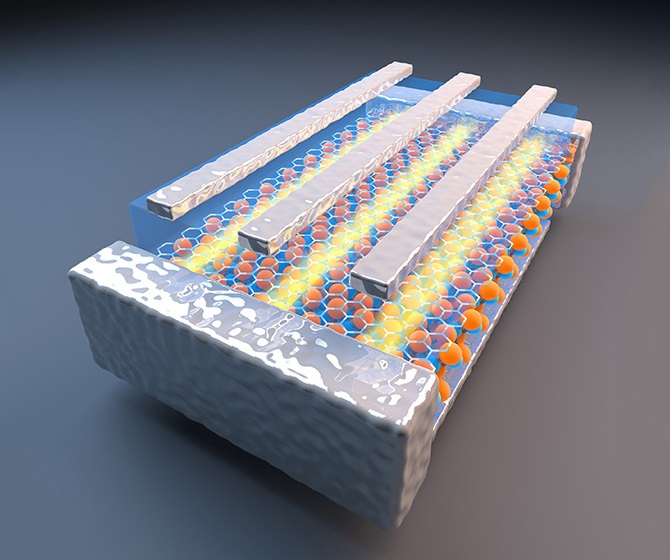

“The high conductivity (of germanium nanowires) makes them ideal for lithium-ion battery applications,” Switzer says.

Switzer’s co-authors on the paper “Electrodeposited Germanium Nanowires” were lead author Naveen K. Mahenderkar, a Ph.D. candidate in materials science and engineering at Missouri S&T; Ying-Chau Liu, a Ph.D. candidate in chemistry at Missouri S&T; and Jakub A. Koza, a postdoctoral associate in Missouri S&T’s Materials Research Center.

Switzer’s research in this area is funded through a $1.22 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Basic Energy Science.