May 7, 2013

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. – Researchers have created a new tool to detect flaws in lithium-ion batteries as they are being manufactured, a step toward reducing defects and inconsistencies in the thickness of electrodes that affect battery life and reliability.

The electrodes, called anodes and cathodes, are the building blocks of powerful battery arrays like those used in electric and hybrid vehicles. They are copper on one side and coated with a black compound to store lithium on the other. Lithium ions travel from the anode to the cathode while the battery is being charged and in the reverse direction when discharging energy.

The material expands as lithium ions travel into it, and this expansion and contraction causes mechanical stresses that can eventually damage a battery and reduce its lifetime, said Douglas Adams, Kenninger Professor of Mechanical Engineering and director of the Purdue Center for Systems Integrity.

The coating is a complex mixture of carbon, particulates that store lithium, chemical binders and carbon black. The quality of the electrodes depends on this "battery paint" being applied with uniform composition and thickness.

"A key challenge is to be able to rapidly and accurately sense the quality of the battery paint," said James Caruthers, Reilly Professor of Chemical Engineering and co-inventor of the new sensing technology.

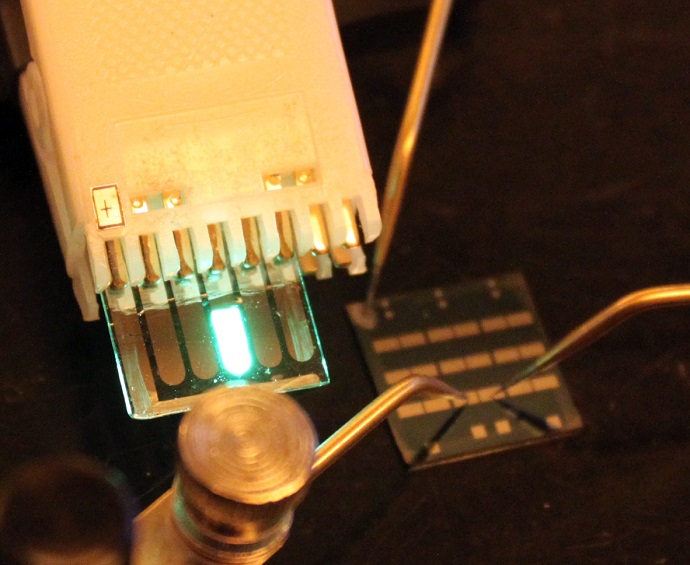

The Purdue researchers have developed a system that uses a flashbulb-like heat source and a thermal camera to read how heat travels through the electrodes. The "flash thermography measurement" takes less than a second and reveals differences in thickness and composition.

"This technique represents a practical quality-control method for lithium-ion batteries," Adams said. "The ultimate aim is to improve the reliability of these batteries."

Findings are detailed in a research paper being presented during the 2013 annual meeting of the Society for Experimental Mechanics, which is June 3-5 in Lombard, Ill. The paper was written by doctoral students Nathan Sharp, Peter O'Regan, Anand David and Mark Suchomel, and Adams and Caruthers.

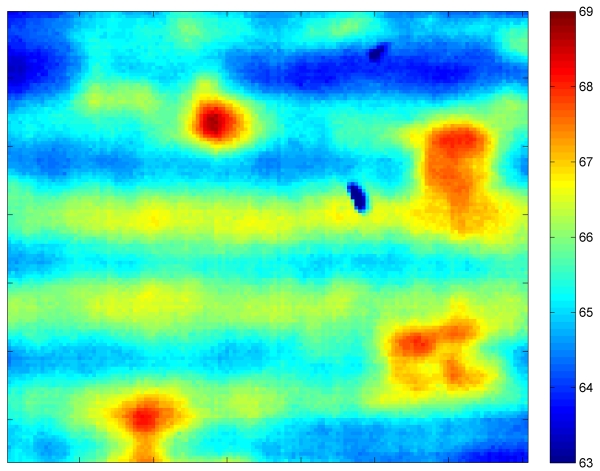

The method uses a flashing xenon bulb to heat the copper side of the electrode, and an infrared camera reads the heat signature on the black side, producing a thermal image.

The researchers found that the viscous compound is sometimes spread unevenly, producing a wavelike pattern of streaks that could impact performance. Findings show the technology also is able to detect subtle differences in the ratio of carbon black to the polymer binder, which could be useful in quality control.

The technique also has revealed various flaws, such as scratches and air bubbles, as well as contaminants and differences in thickness, factors that could affect battery performance and reliability.

"We showed that we can sense these differences in thickness by looking at the differences in temperature," Adams said. "When there is a thickness difference of 4 percent, we saw a 4.8 percent rise in temperature from one part of the electrode to another. For 10 percent, the temperature was 9.2 percent higher, and for 17 percent it was 19.2 percent higher."

The thermal imaging process is ideal for a manufacturing line because it is fast and accurate and can detect flaws prior to the assembly of the anode and cathodes into a working battery.

"For example, if I see a difference in temperature of more than 1 degree, I can flag that electrode right on the manufacturing floor," Adams said. "The real benefit, we think, is not just finding flaws but also being able to fix them on the spot."

Purdue has applied for a patent on the technique.