DECEMBER 04, 2013

A new technique developed at Berkeley Lab’s Advanced Light Source could help scientists better understand and improve the materials required for high-performance lithium-ion batteries that power EVs and other applications.

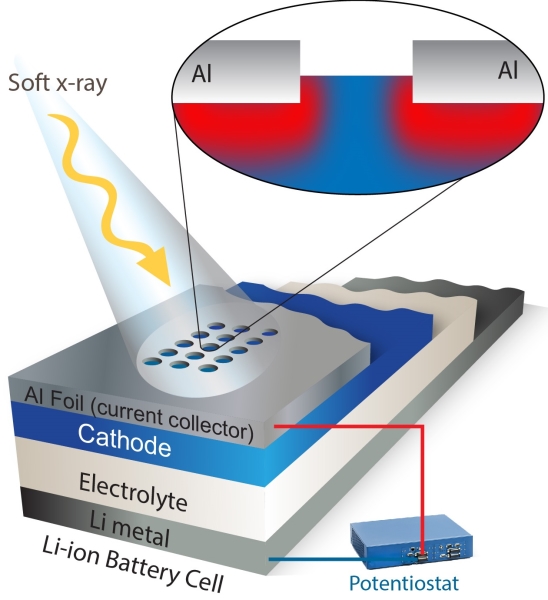

The technique, which uses soft X-ray spectroscopy, measures something never seen before: the migration of ions and electrons in an integrated, operating battery electrode.

Over the past several years, scientists have developed several ways to study the changes in a working electrode. These include techniques based on hard X-rays, electron microscopy, neutron scattering, and nuclear magnetic resonance imaging.

But most of these methods track structural changes. They don’t track electron and ion dynamics directly, which is very important in the push to understand and optimize battery performance.

“In order to improve battery materials, we need to study charge dynamics in a complete electrode while it’s operating – and our approach does that,” says Wanli Yang, a scientist at Berkeley Lab’s Advanced Light Source who developed the technique with Gao Liu of Berkeley Lab’s Environmental Energy Technologies Division.

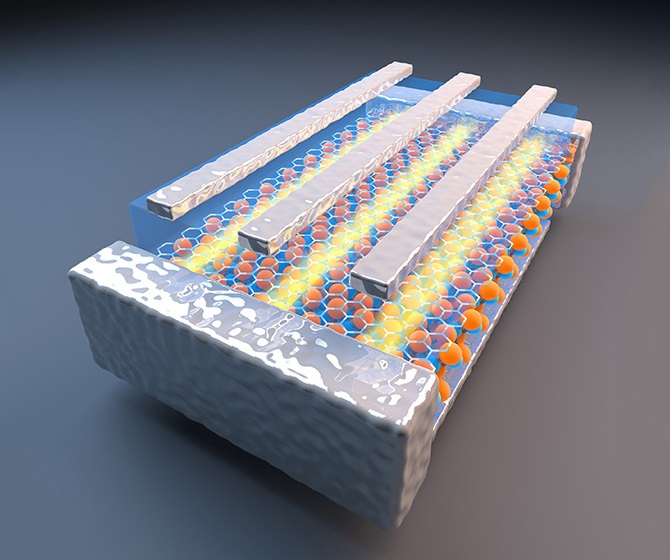

Their technique can also analyze charge dynamics in an integrated lithium-ion electrode, not just an electrode’s individual components. This is important because an electrode is a complex system consisting of active materials, electrolyte, binder and additives, which are attached to a metallic current collector.

As reported in a recent issue of the journal Nature Communications, their approach is already yielding insights into how lithium-ion battery electrodes charge. For example, Yang and Liu used it to study a lithium-ion cathode made of nickel, manganese, and cobalt. They found that its “electrochemical state of charge” is uniformly distributed across the electrodes as it charges.

They also studied a different lithium-ion cathode made of iron and phosphate—and found some surprises. The phase transformation starts near the current collectors, and then it takes hours of relaxation time before the electrodes’ “electrochemical state of charge” is uniformly distributed.

This counters conventional wisdom about the charging process of lithium-ion battery electrodes, which indicates that theoretical simulations and further experiments are needed to shed light on the phenomenon, the scientists say.

Adds Liu, “This comparative study reveals the power of in situ soft X-ray spectroscopy to reveal the charge dynamics in battery electrodes. Ultimately, studying the microscopic mechanisms of charge dynamics will help researchers design better battery materials.”

The new technique relies on the Advanced Light Source, a Department of Energy national user facility located at Berkeley Lab that generates intense light for scientific research. The facility emits soft X-rays, which are very good at interacting with electrons. Because of this, soft X-ray spectroscopy is an ideal probe for studying battery characteristics such as electron and ion diffusion.

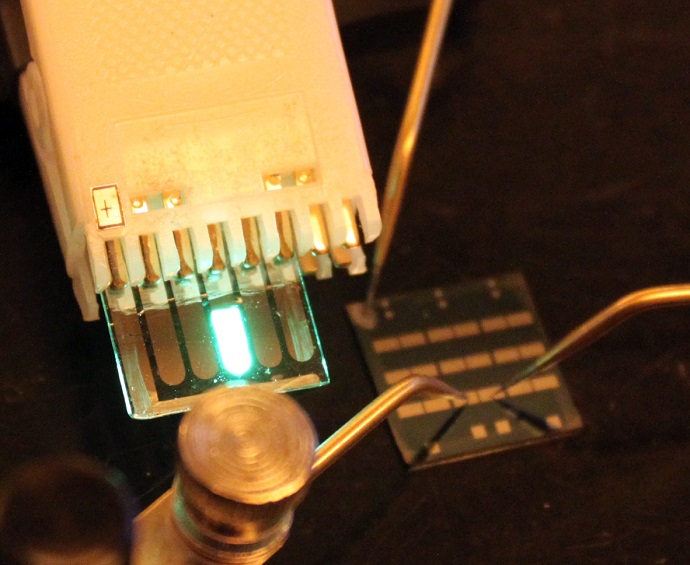

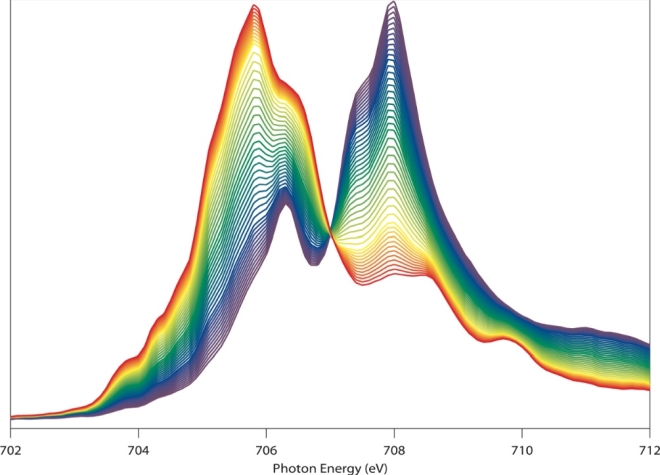

Yang calls this image a “beautiful butterfly.” That’s partly because it looks like one. But it’s also because the image, obtained via soft x-ray spectroscopy at the Advanced Light Source, vividly reveals the chemical and physical changes of the electrode material during battery operation. The sensitive probe could clarify the charge and discharge mechanism of battery electrodes, and fingerprint the migration of the electrons and ions.

There was one big obstacle, however. Soft X-rays are so-named because they don’t penetrate very far, only about 100 nanometers, which isn’t far enough to study an electrode covered by a metal foil.

To overcome this, the spectroscopists at the Advanced Light Source worked with battery experts in the Environmental Energy Technologies Division. The team employed a laser system to etch a special detection window on the top foil layer. This allows soft X-rays to penetrate into an electrode and measure what the electrons and ions are up to.

“The shallow probe depth of soft X-rays becomes an advantage in this case because it provides the chance to obtain position-sensitive information on the electron and ion migration,” says Yang.

This research was performed at beamline 8.0.1 at the Advanced Light Source, with battery cells assembled at the Environmental Energy Technologies Division. It was funded in part by the Energy Department’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy and Berkeley Lab’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development Program.

The Advanced Light Source is a third-generation synchrotron light source producing light in the x-ray region of the spectrum that is a billion times brighter than the sun. A DOE national user facility, the ALS attracts scientists from around the world and supports its users in doing outstanding science in a safe environment. For more information visit www-als.lbl.gov.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world’s most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab’s scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. For more, visit www.lbl.gov.