May 1, 2013

By mimicking the bulging, bowl-shaped eyes possessed by dragonflies, praying mantises, houseflies and other insects, a team of researchers that includes a University of Colorado Boulder engineer has built an experimental digital camera that can take exceptionally wide-angle photos without distorting the image.

To create the innovative camera, which also allows for a practically infinite depth of field, the scientists used stretchable electronics and a pliable sheet of microlenses made from a material similar to that used for contact lenses. The researchers described the camera in an article published today in the journal Nature.

Conventional wide-angle lenses, such as fisheyes, distort the images they capture at the periphery, a consequence of the mismatch of light passing through a hemispherically curved surface of the lens only to be captured by the flat surface of the electronic detector.

For the digital camera described in the new study, the researchers were able to create an electronic detector that can be curved into the same hemispherical shape as the lens, eliminating the distortion.

“The most important and most revolutionizing part of this camera is to bend electronics onto a curved surface,” said Jianliang Xiao, assistant professor of mechanical engineering at CU-Boulder and co-lead author of the study. “Electronics are all made of silicon, mostly, and silicon is very brittle, so you can’t deform the silicon. Here, by using stretchable electronics we can deform the system; we can put it onto a curved surface.”

Creating a camera inspired by the compound eyes of arthropods — animals with exoskeletons and jointed legs, including all insects as well as scorpions, spiders, lobsters and centipedes, among other creatures — has been a sought-after goal. Compound eyes typically have a lower resolution than the eyes of mammals, but they give arthropods a much larger field of view than mammalian eyes as well as high sensitivity to motion and an infinite depth of field.

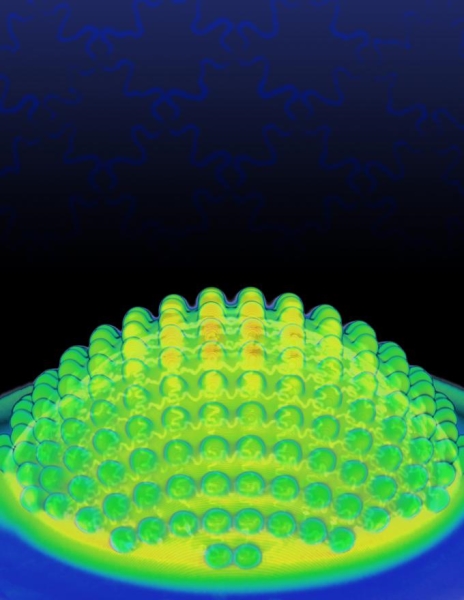

Compound eyes consist of a collection of smaller eyes called ommatidia, and each small eye is made up of an independent corneal lens as well as a crystalline cone, which captures the light traveling through the lens. The number of ommatidia determines the resolution and varies widely among arthropods. Dragonflies, for example, have about 28,000 tiny eyes while worker ants have only in the neighborhood of 100.

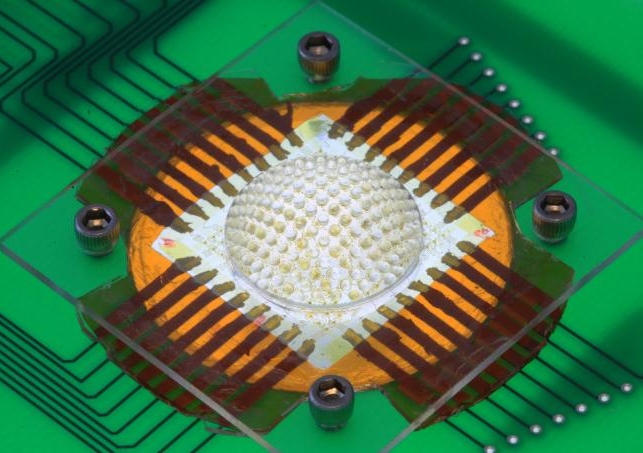

Imitating the corneal lens-crystalline cone pairings, the camera created by Xiao and his colleagues has 180 miniature lenses, each of which is backed with its own small electronic detector. The number of lenses used in the camera is similar to the number of ommatidia in the compound eyes of fire ants and bark beetles.

The electronics and the lenses are both flat when fabricated, said Xiao, who began working on the project as a postdoctoral researcher in John Roger’s lab at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. This allows the product to be manufactured using conventional systems.

“This is the key to our technology,” Xiao said. “We can fabricate an electronic system that is compatible with current technology. Then we can scale it up.”

The lens sheet and the electronics sheet are integrated together while flat and then molded into a hemispherical shape afterward. Each individual electronic detector and each individual lens do not deform, but the spaces between the detectors and lenses can stretch and allow for the creation of a new 3-D shape. The electronic detectors are all attached with serpentine filament bridges, which are not compromised as the material stretches and bends.

An image of the experimental camera built to mimic the eyes of arthropods. Credit John Rogers, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

In the pictures taken by the new camera, each lens-detector pairing contributes a single pixel to the image. Moving the electronic detectors directly behind the lenses — instead of having just one detector sitting farther behind a single lens, as in conventional cameras — creates a very short focal length, which allows for the near-infinite depth of field.

The new paper demonstrates that stretchable electronics can be used as the foundation for a distortion-free hemispherical camera, but commercial production of such a camera may still be years away, Xiao said.

The three other co-lead authors of the paper are Young Min Song, Yizhu Xie and Viktor Malyarchuk, all of the University of Illinois. Other co-authors are Ki-Joong Choi, Rak-Hwan Kim and John Rogers, also of Illinois; Inhwa Jung, of Kyung Hee University in Korea; Zhuangjian Liu, of the Institute of High Performance Computing A*star in Singapore; Chaofeng Lu, of Zhejiang University in China and Northwestern University; Rui Li, of Dalian University of Technology in China; Kenneth Crozier, of Harvard University; and Yonggang Huang, of Northwestern University.

The research was funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the National Science Foundation.

For more information: