March 30, 2016

So you think the gold in your ring or watch came from a mine in Africa or Australia? Well, think farther away. Much, much farther.

Michigan State University researchers, working with colleagues from Technical University Darmstadt in Germany, are zeroing in on the answer to one of science’s most puzzling questions: Where did heavy elements, such as gold, originate?

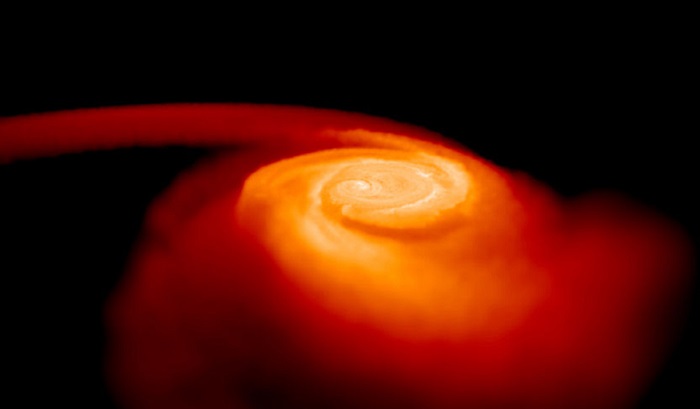

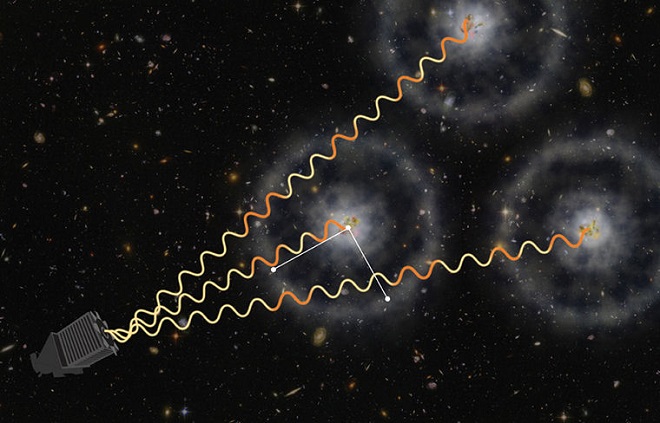

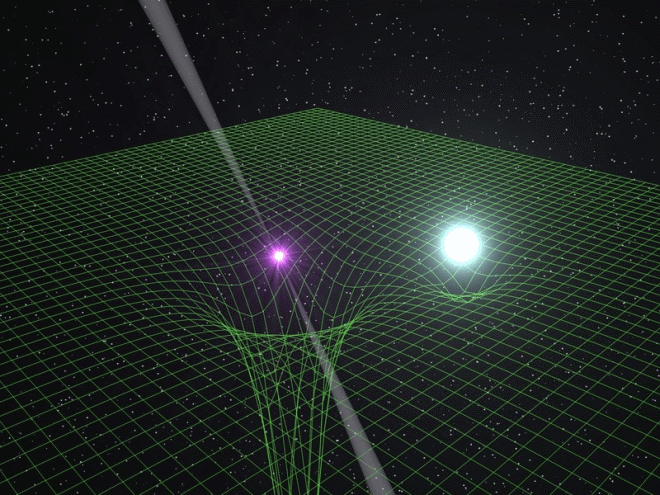

Currently there are two candidates, neither of which are located on Earth – a supernova, a massive star that, in its old age, collapsed and then catastrophically exploded under its own weight; or a neutron-star merger, in which two of these small yet incredibly massive stars come together and spew out huge amounts of stellar debris.

In a recently published paper in the journal Physical Review Letters, the researchers detail how they are using computer models to come closer to an answer.

Witold Nazarewicz is a professor at the MSU-based Facility for Rare Isotope Beams. He is a member of a research team that is trying to determine the stellar origins of gold and other heavy metals in the universe. A paper on the subject was published in the journal Physical Review Letters. Photo courtesy of FRIB.

“At this time, no one knows the answer,” said Witold Nazarewicz, a professor at the MSU-based Facility for Rare Isotope Beams and one of the co-authors of the paper. “But this work will help guide future experiments and theoretical developments.”

By using existing data, often obtained by means of high-performance computing, the researchers were able to simulate production of heavy elements in both supernovae and neutron-star mergers.

“Our work shows regions of elements where the models provide a good prediction,” said Nazarewicz, a Hannah Distinguished Professor of Physics who also serves as FRIB’s chief scientist. “What we can do is identify the critical areas where future experiments, which will be conducted at FRIB, will work to reduce uncertainties of nuclear models.”

Other researchers included Dirk Martin and Almudena Arcones from Technical University Darmstadt and Erik Olsen of MSU.

MSU is establishing FRIB as a new scientific user facility for the Office of Nuclear Physics in the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science.

Under construction on campus and operated by MSU, FRIB will enable scientists to make discoveries about the properties of rare isotopes in order to better understand the physics of nuclei, nuclear astrophysics, fundamental interactions, and applications for society, including in medicine, homeland security and industry.