March 4, 2015

Some of the galaxies in our universe are veritable star nurseries. For example, our own Milky Way produces, on average, at least one new star every year. Others went barren years ago, now producing few if any new stars.

Why that happens is a question that has dogged astronomers for years. But now, more than 20 years of research by a team led by Michigan State University has culminated in what might be the answer to that elusive question.

According to a study published in the journal Nature, galactic “rain” may be the key to whether a galaxy is fertile.

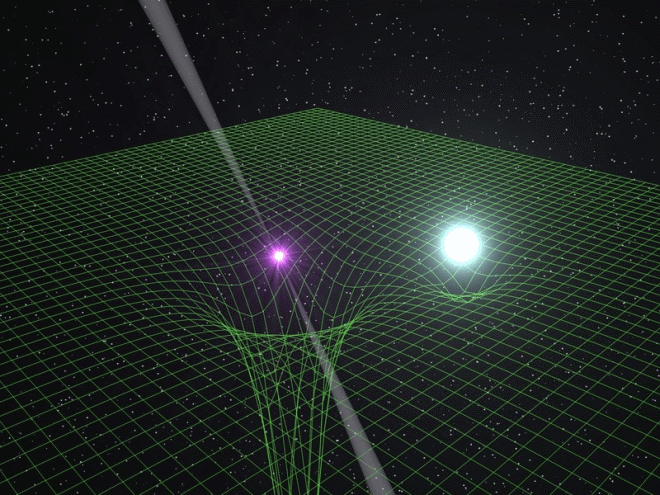

“We know that precipitation can slow us down on our way to work,” said Mark Voit, an MSU professor of physics and astronomy who led the research team. “Now we know it can also slow down star formation in galaxies with huge black holes.”

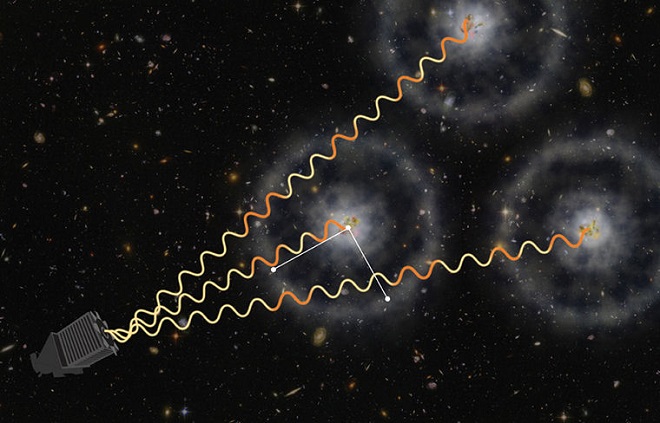

Obviously it’s not in the form of rain or snow, but rather cool gas that helps make the creation of stars possible. When conditions are right, these cooling gas clouds help make stars. However, some of the clouds fall into the massive black holes that reside at the center of the galaxy clusters. That triggers the production of jets that reheat the gas like a blowtorch, preventing more stars from forming.

The researchers, using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, analyzed X-rays from more than 200 galaxy clusters. They could pinpoint how this process of precipitation affects the environment around some of the universe’s largest black holes.

The galaxies within these clusters are surrounded by enormous atmospheres of hot gas that normally would cool and form many stars. However, this is not what astronomers see. Usually there are only feeble amounts of stars forming.

“Something is limiting the rate at which galaxies can turn that gas into stars and planets,” Voit said. “I think we’re finally getting a handle on how this all works.”

While precipitation plays a key role in some galaxies, the researchers found other galaxies where the precipitation had shut off. In these galaxies, the movement of heat around the central galaxy, perhaps due to a collision with another galaxy cluster, likely “dried up” the precipitation around the black hole.

A galaxy cluster can contain anywhere from 50 to 1,000 galaxies. The Milky Way is part of a cluster known as the Local Group, which contains about 50.

In addition to adding to the knowledge of how our universe operates, Voit said research like this helps us all stretch beyond what we thought was possible.

“Astronomy gets people’s attention,” he said. “It makes people curious. It motives them to learn more. What astronomy does is help sustain our culture of discovery.”

Other members of the research team were Megan Donahue, MSU professor of physics and astronomy; Michael McDonald of MIT; and Greg Bryan of Columbia University.