July 25, 2014

An international team of astronomers, including Harald Ebeling of the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa’s Institute for Astronomy, has used the Hubble Space Telescope to map the mass within a galaxy cluster, originally discovered with Maunakea telescopes, more precisely than ever before.

Clusters of galaxies are the most massive objects in the universe, comprising hundreds to thousands of galaxies and also enormous amounts of invisible dark matter. They grow through collisions in which smaller clusters merge into ever more massive systems, a process that can temporarily lead to highly complex mass distributions.

Ebeling specializes in finding the rarest, most extreme clusters that are the most rewarding targets for detailed studies of the formation and evolution of cosmic structure. One of the clusters discovered by Ebeling’s team in the course of the Massive Cluster Survey (MACS), which used several telescopes on Maunakea, goes by the name of MACSJ0416.1-2403.

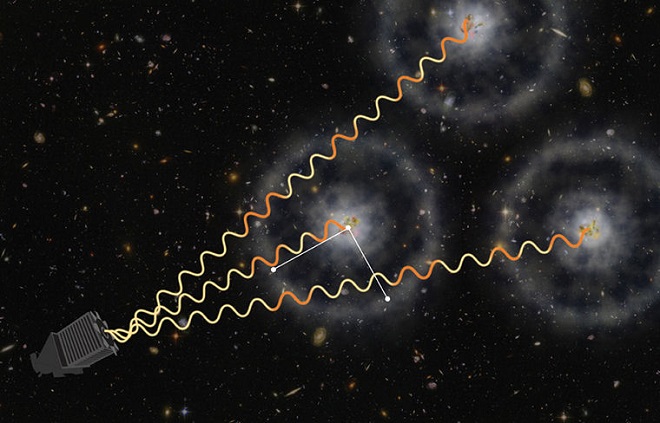

It was found to be so massive that the cluster was selected for extremely deep observations with the Hubble Space Telescope as part of the Frontier Fields program. The resulting Hubble data show the galaxy distribution within the cluster in stunning detail. The new, ultra-deep observations also reveal a multitude of distorted images of galaxies that are in fact far behind the cluster, bent and often appearing multiple times within the Hubble image of MACSJ0416 due to an effect called gravitational lensing, in which the mass of a foreground object magnifies and distorts more distant objects.

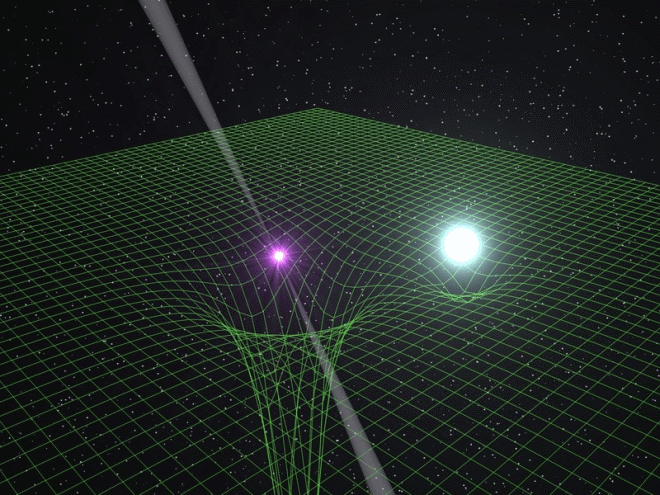

Gravitational lensing by mass concentrations in space comes in two varieties: so-called “strong lensing,” which creates the highly elongated, almost linear images of distant background galaxies visible near the center of the cluster (as predicted by Einstein’s theory or relativity), and “weak lensing,” pioneered by IfA’s Nick Kaiser in the 1990s, which causes much less perceptible, faint, statistical distortions of hundreds of background galaxies viewed at larger distances from the cluster core.

The spectacular images collected by MACSJ0416 during the Frontier Fields program were recently analyzed by members of the team led by Mathilde Jauzac (Durham University, UK and Astrophysics and Cosmology Research Unit, South Africa). They used both strong and weak-lensing techniques to infer the cluster mass distribution that creates the many lensing features identified in these data.

Their meticulous search for even the faintest gravitational lensed images was unprecedentedly successful, resulting in the identification of four times as many lensed background galaxies as were previously known in this system. The result is a mass map of MACSJ0416 that is more precise than any ever derived for any galaxy cluster, showing the highly elongated distribution of dark matter in this merging cluster in great detail and over an enormous range of scales. The study also established MACSJ0416 as a huge cluster indeed, with a measured mass of 160 trillion times the mass of the sun.

“Our analysis of the Frontier Fields data demonstrates impressively how detailed studies of the extremely massive clusters found by MACS can advance our understanding not only of the complexity of cluster formation but in fact of the distant universe behind these powerful gravitational lenses,” explains Ebeling.

Further investigations of MACSJ0416 are underway, combining the Frontier Fields images with deep X-ray observations of the hot gas within the cluster and the spectroscopic redshifts of the cluster galaxies, measured by Ebeling as part of the follow-up work conducted by the MACS team using Maunakea facilities. Their primary goal is to deduce the merger history of this extreme cluster by establishing its three-dimensional geometry and the trajectories of the clusters involved in the collision.

The results of the study will be published in Monthly notices of the Royal Astronomical Society in July 2014. Read the European Space Agency press release for more information.