July 31, 2014

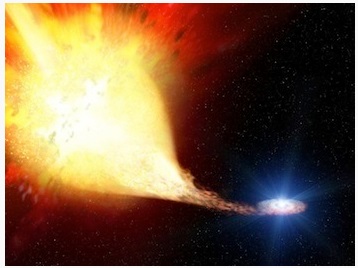

High-energy observations with the INTEGRAL space observatory have revealed a surprising signal of gamma-rays from the surface of material ejected by a recent supernova explosion. This result challenges the prevailing explosion model for type Ia supernovae, indicating that such energetic events might be ignited from the outside as well – rather than from the exploding dwarf star’s centre. The scientists from the Max Planck Institutes for Extraterrestrial Physics and for Astrophysics present their findings in the current edition of Science to the astronomical community.

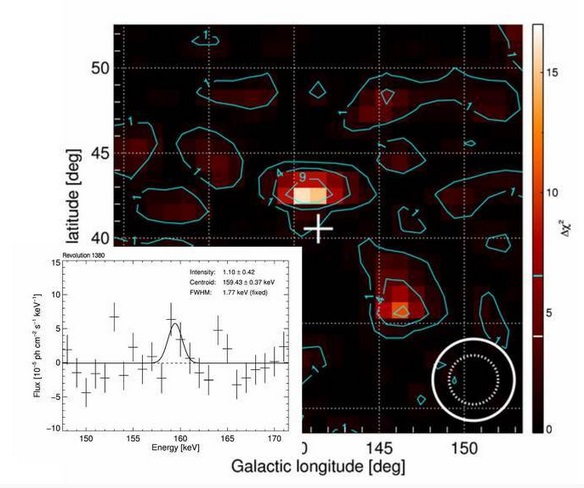

In January, a supernova explosion, called SN2014J, was reported in a nearby starburst galaxy, called M82. Just two weeks later, astronomers were able to take data with the INTEGRAL space telescope, revealing two characteristic gamma-ray lines from a radioactive nickel isotope (56Ni).

Supernovae are giant nuclear fusion furnaces, and the atomic nuclei of nickel are believed to be the main product of nuclear fusion inside the supernova. Presumably this radioactive element is created mainly in the centre of the exploding white dwarf star and therefore occulted from direct observation. As the explosion dilutes the entire stellar material, the outer layers get more and more transparent, and after several weeks to months also gamma-rays from the nickel decay chain are expected to be accessible to observation.

As the astronomers scrutinized the new data, however, they found traces of the decay of radioactive nickel just 15 days after the presumable explosion date. This implies that the observed material was near the surface of the explosion, which was a surprise.

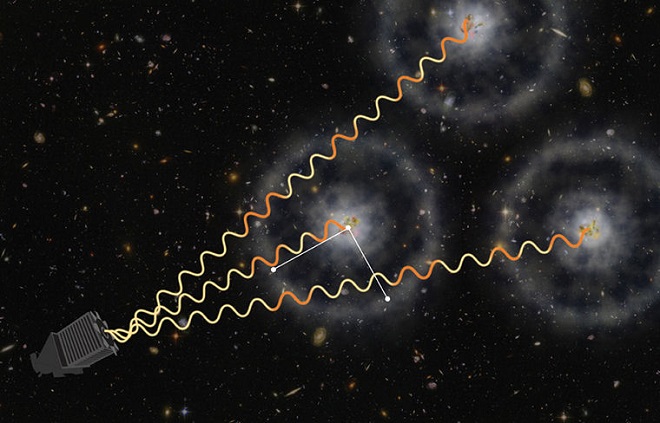

Detection of a nickel line in the Supernova SN2014J, some two weeks after the explosion. The position of the signal agrees within the measurement error with the position of the supernova (indicated by the cross).

“For quite a while, we were puzzled by this surprising signal”, says Roland Diehl from the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, the lead author of the study and Principal Investigator of the INTEGRAL spectrometer instrument. “But we could not find anything wrong, rather the gamma-ray lines from 56Ni faded away as expected after a few days, and clearly came from the direction of the supernova”, he explains the outcome of their analysis of the observations. At MPE, an expert analysis team has been developing special methods for high-resolution spectroscopy of gamma-ray lines for many years. This has been successfully applied to the study of nucleosynthesis throughout our Galaxy as well as for the Cassiopeia A supernova remnant - and now to the recent supernova observations.

“We know that the supernova burns an entire white dwarf star within a second, but we are not sure how the explosion is ignited in the first place”, explains Wolfgang Hillebrandt, a co-author of the study from the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics. “A companion star’s action seems required”, he continues, “and for a while, we believed that only those white dwarfs explode, which are loaded with material from the companion star until they reach a critical limiting mass.” But then, the explosion would be ignited in the core of the white dwarf, and no nuclear fusion products should be seen on the outside.

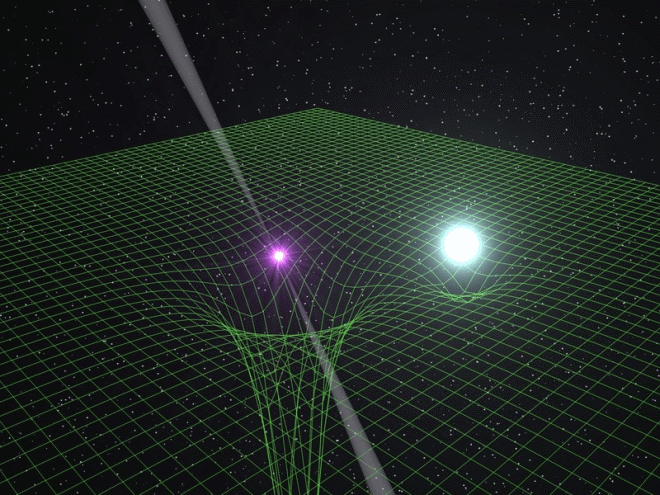

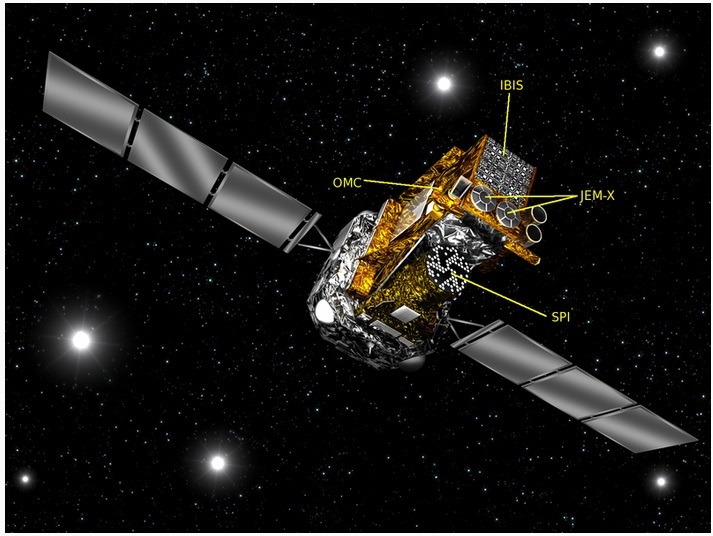

The INTEGRAL Space Observatory for gamma-rays from cosmic sources.

© ESA

Diehl, Hillebrandt, and their colleagues had argued over the result for a while, challenging the methods of data analysis as well as ideas about supernova explosion scenarios. They now report their finding, supported by statistical arguments, and their descriptions of their methods to help scientists judge this important discovery. They conclude that those gamma-rays shed new light on how a binary companion’s material flow can ignite such a supernova from outside, and without demand for exceeding a critical mass limit for white dwarf stars.

From the early appearance of the nickel gamma-rays it seems that some modest amount of outer material accreted from the companion star ignited, and was processed to fusion ashes including the observed nickel. This primary explosion then must have triggered the main supernova, which was also observed with a variety of telescopes at many other wavelength bands, and appears as a rather normal supernova in these observations.

Gamma-rays from radioactive decay directly trace nuclear fusion ashes, and thus make a unique contribution to what we can learn about such explosions. The scenario that the astrophysicists describe ties in with recent belief that rather rapid material flows such as they occur in merging white dwarfs may often be the origins of supernovae of this type.

About INTEGRAL

The INTEGRAL gamma-ray space observatory was launched in 2002 for a nominal 3-year mission, and now, after almost 12 years, is still in good shape for many more years of observations. Together with the partner institute IRAP/CESR in Toulouse, MPE was responsible for one of the two main telescopes, the SPI spectrometer. INTEGRAL has discovered many new sources of the violent high-energy universe, among them active galaxies, new classes of accreting binary systems and pulsars, gamma-ray bursters, and surveys of nucleosynthesis gamma-rays from different sources plus a puzzling signal from annihilation of antimatter.

INTEGRAL is a mission of the European Space Agency ESA in cooperation with Russia and the United States.

Website: http://sci.esa.int/integral/