27 June 2014

When Albert Einstein proposed the existence of gravitational waves as part of his theory of relativity, he set in train a pursuit for knowledge that continues nearly a century later.

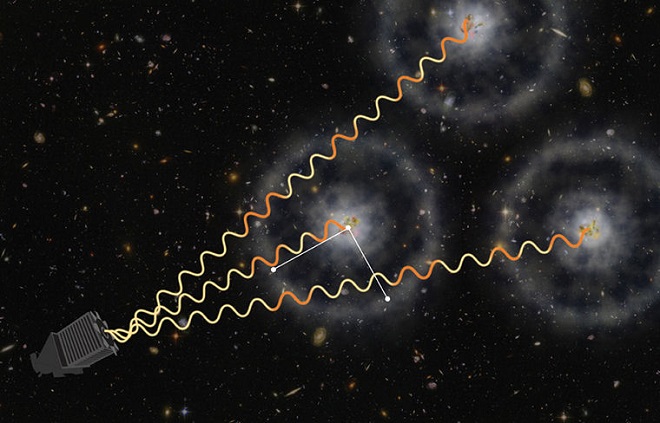

These ripples in the space-time continuum exert a powerful appeal because it is believed they carry information that will allow us to look back into the very beginnings of the universe. But although the weight of evidence continues to build, undisputed confirmation of their existence still eludes scientists.

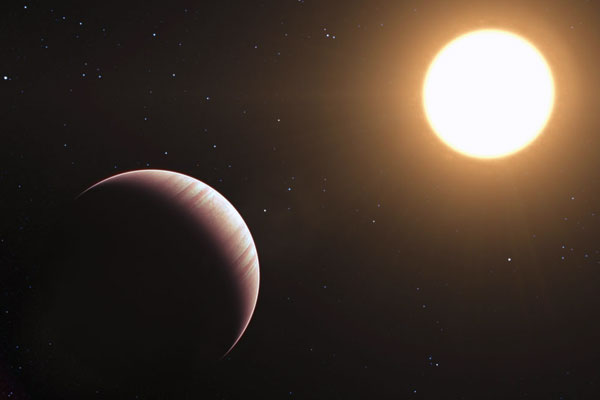

Researchers from University of Warwick and Monash University have provided another piece of the puzzle with their precise measurements of a rapidly rotating neutron star: one of the smallest, densest stars in the universe.

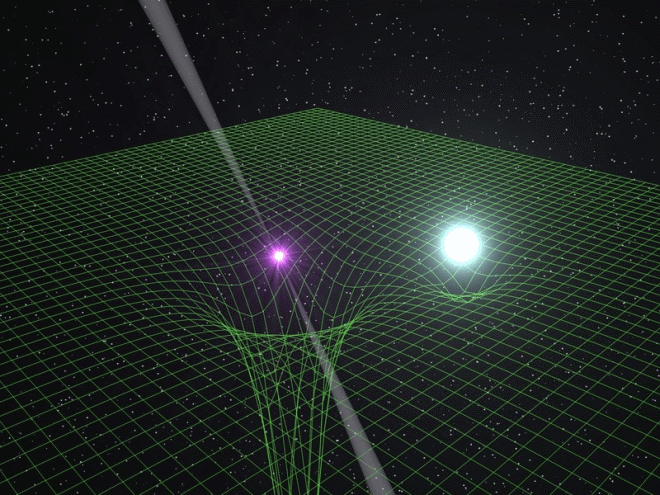

Neutron stars, along with colliding black holes and the Big Bang, may all be sources of gravitational waves.

In work published in The Astrophysical Journal, the Monash and Warwick scientists significantly improved the precision with which they could measure the orbit of Scorpius X-1, a double star system containing a neutron star that feeds off a nearby companion star. This interaction makes it the strongest source of X-rays in the sky apart from the sun.

Dr Duncan Galloway from the Monash Centre for Astrophysics said that the main difficulty in searching for gravitational waves emitted by Scorpius X-1 was the lack of precise knowledge about the neutron star’s orbit.

“We have made a concerted effort to refine Scorpius X-1’s orbit and other parameters, with the goal of significantly boosting the sensitivity of searches for gravitational waves,” Dr Galloway said.

“Detecting gravitational waves will open a new window for observation and allow us to study objects in the universe in a way that can’t be achieved using traditional astronomy techniques.”

Monash PhD student Ms Shakya Premachandra spent three months at the University of Warwick learning specific techniques and methods to improve the team’s measurements.

Under the guidance of Dr Danny Steeghs from Warwick’s Astronomy and Astrophysics Group, Ms Premachandra worked on the research data and learnt a specific software program developed by Warwick astronomers.

Dr Steeghs said he first started researching gravitational waves with Monash in 2009 and seed funding from the Monash Warwick Alliance has supported these efforts.

“With help from the Monash Warwick Alliance, we quickly identified a genuine opportunity to make substantial research progress by combining our expertise, which also led to an ambitious plan for continued collaboration,” Dr Steeghs said.

Dr Galloway and Ms Premachandra are members of the LIGO Scientific Collaboration, a world-wide network of more than 800 astronomers. Its work is complementary to that of the BICEP collaboration, which last month made headlines with its analysis of gravitational waves in the afterglow of the Big Bang, called the cosmic microwave background.

The Monash Warwick Alliance, which supports this research project and many others, is an innovative approach to higher education that is accelerating the exchange of people, ideas and information between Monash and Warwick Universities.