22 JANUARY 2014

An international team, including researchers from CNRS and the Paris Observatory at LESIA (Observatoire de Paris/CNRS/Université Pierre et Marie Curie/Université Paris-Diderot) and at IMCEE (Observatoire de Paris/CNRS/Université Pierre et Marie Curie/Université Lille 1), has discovered intermittent emissions of water vapor on Ceres, the largest of the asteroids, using the Herschel space telescope. These findings are published in the journal Nature dated 23 January 2014.

Ceres, the first asteroid ever identified, was discovered in 1801 by Giuseppe Piazzi in Sicily. It is also the largest of the asteroids, with a diameter of around 950 km, and is now classified as a dwarf planet, like Pluto. It is located in the main asteroid belt (between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter), accounting for one fifth of its total mass.

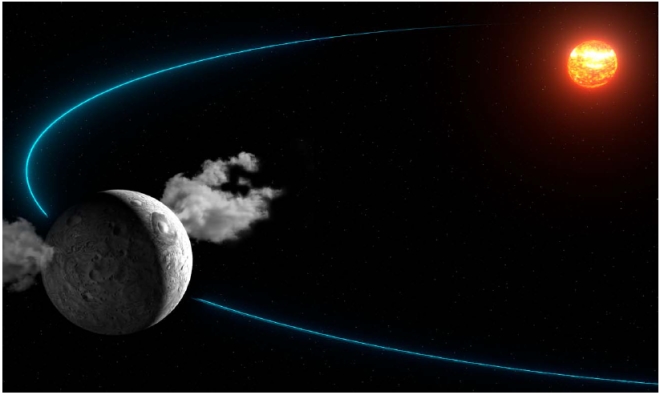

The presence of water on the surface of Ceres has been suspected for over thirty years. Using the Herschel space telescope, the team of astronomers had already clearly detected the presence of water in gaseous form around Ceres on several occasions in 2012 and 2013. However, the water vapor is only emitted when Ceres, whose orbit is not perfectly circular, is at its closest point to the Sun. The astronomers were able to determine that the water was ejected from two well localized sources, rather like two giant geysers. Using a model of cometary jets developed at LESIA, they were even able to show that part of this water vapor fell back onto Ceres.

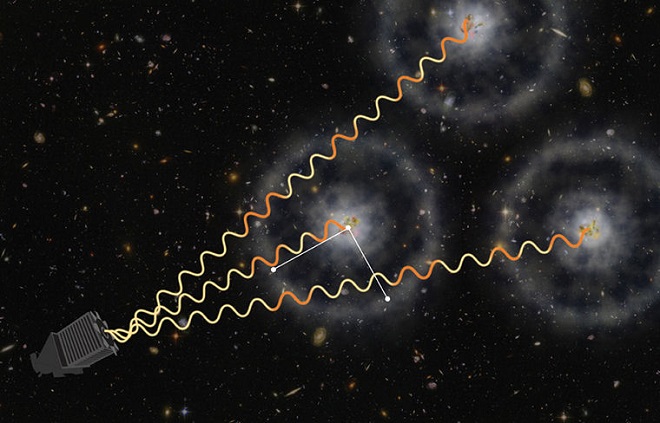

The discovery puts an end to a scientific controversy that had lasted since the late 1970s. A signature in the near infrared in the spectrum of Ceres was considered by some researchers as showing the presence of ice on its surface, whereas other researchers attributed it simply to certain minerals in the asteroid. Although the photodissociation product of water around Ceres was detected marginally in 1992, the observation was never subsequently confirmed, despite various attempts including the European Southern Observatory (ESO)'s Very Large Telescope (VLT).

Although there is now clear evidence of the emission of water vapor from Ceres, which can easily be explained by cometary behavior, the question of the origin of the water remains open. Does Ceres have a subsurface ocean? Or do these two regions correspond to two isolated pockets? If this is the case, what is their origin? NASA's Dawn spacecraft, launched in 2007, is currently heading for Ceres after studying the asteroid Vesta in 2011. Expected in 2015, high resolution images and spectra of the surface of Ceres should help us to better understand the origin of the geysers.

The presence of water on Ceres has major implications for our general understanding of the origin of water in the Solar System, and in particular on Earth. Traditionally, the primitive Solar System is viewed as being divided into a 'dry' zone and an ice-rich zone, with the boundary between them corresponding approximately to Jupiter's orbit. The presence of water on Ceres would therefore be in agreement with the latest models of the evolution of the Solar System, which show that the migration of planets led to a mixing between asteroids and comets, resulting in today's main belt made up of a host of diverse bodies. This migration placed large numbers of water-rich objects into orbits crossing that of Earth, thus providing it with the water that makes up its oceans.

Reference

Localized sources of water vapour on the dwarf planet (1) Ceres, Michael Küppers, Laurence O'Rourke, Dominique Bockelée-Morvan, Vladimir Zakharov, Seungwon Lee, Paul von Allmen, Benoît Carry, David Teyssier, Anthony Marston, Thomas Müller, Jacques Crovisier, M. Antonietta Barucci & Raphael Moreno, Nature, 23 January 2014.

doi : 10.1038/nature12918