17 April 2013

Durham University astronomers have played a key role in research using a powerful new telescope to bring images of the distant Universe into much sharper focus.

Fertile star-forming galaxies that were highly active when the Universe was at a relatively youthful age – less than three billion years old – can now be seen in images that are significantly sharper than anything previously possible.

The international team has used the newly-launched ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) telescope to pinpoint the locations of more than 100 of the most fertile star-forming galaxies in the early Universe.

ALMA, located in the high altitude desert of northern Chile and made up of 66 high precision radio antennas, is so powerful that in just a few hours it captured as many observations of these galaxies as have been made by all similar telescopes worldwide over a span of more than a decade.

Dr Mark Swinbank, of Durham University’s Department of Physics, co-authored a paper on the research.

He said: “ALMA has provided us with images of the distant Universe which are 200 times sharper than anything previously possible. The data robustly identify some of the most active and rapidly star-forming galaxies that have ever occurred.

“Many of the galaxies we identify are seen when the Universe was less than three billion years old (about 20% of its current age). Our images show that these galaxies are forming stars more than 100 times faster than our own galaxy, the Milky Way, and represent a phase of galaxy evolution that all local, massive galaxies are likely to have passed through.”

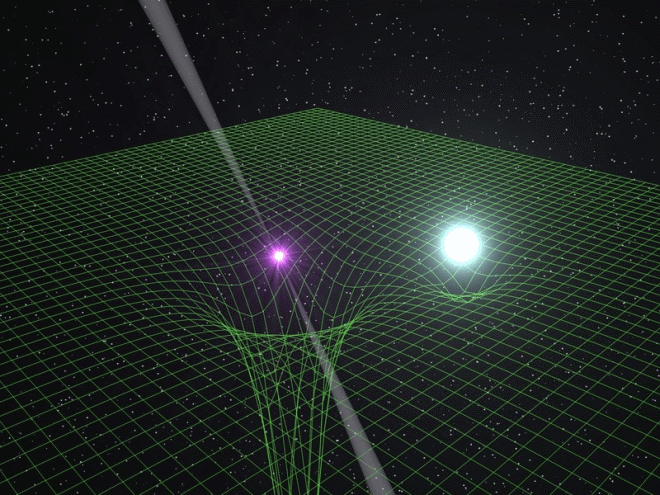

The most fertile bursts of star birth in the early Universe took place in distant galaxies containing lots of cosmic dust. These galaxies are of key importance to our understanding of galaxy formation and evolution over the history of the Universe, but the dust obscures them and makes them difficult to identify with visible-light telescopes. To pick them out, astronomers must use telescopes that observe light at longer wavelengths, around one millimetre, such as ALMA.

“ALMA is so powerful that it has revolutionised the way that we can observe these galaxies, even though the telescope was not fully completed at the time of the observations,” said lead author Dr Jacqueline Hodge, from the Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie in Heidelberg, Germany.

Dr Alexander Karim, of Durham University, said: “We previously thought the brightest of these galaxies were forming stars a thousand times more vigorously than our own galaxy, the Milky Way, putting them at risk of blowing themselves apart. The ALMA images revealed multiple, smaller galaxies forming stars at somewhat more reasonable rates.”

The results form the first statistically reliable catalogue of dusty star-forming galaxies in the early Universe, and provide a vital foundation for further investigations of these galaxies’ properties at different wavelengths, without risk of misinterpretation due to the galaxies appearing blended together.

The best map so far of these distant dusty galaxies was made using the European Southern Observatory-operated Atacama Pathfinder Experiment telescope (APEX). It surveyed a patch of the sky about the size of the full Moon and detected 126 such galaxies.

But in the APEX images, each burst of star formation appeared as a relatively fuzzy blob, which might be so broad that it covered more than one galaxy in sharper images made at other wavelengths. Without knowing exactly which of the galaxies were forming the stars, astronomers were hampered in their study of star formation in the early Universe.

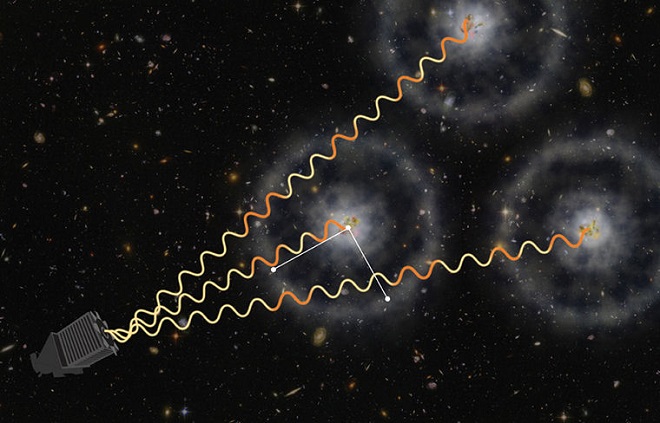

Pinpointing the correct galaxies requires sharper observations, and sharper observations require a bigger telescope. While APEX has a single 12-metre-diameter dish-shaped antenna, telescopes such as ALMA use multiple APEX-like dishes spread over wide distances. The signals from all the antennas are combined, and the effect is like that of a single, giant telescope as wide as the whole array of antennas.

Not only could the team unambiguously identify which galaxies had regions of active star formation, but in up to half the cases they found that multiple star-forming galaxies had been blended into a single blob in the previous observations. ALMA’s sharp vision enabled them to distinguish the separate galaxies.