19 November 2014

SPACE: Astronomers have observed a mysterious phenomenon, which could be a massive black hole that has been ejected into space in connection with two galaxies colliding. This may be due to gravitational waves from the collision. The results are published in the scientific journal Monthly Notices, Royal Astronomical Society.

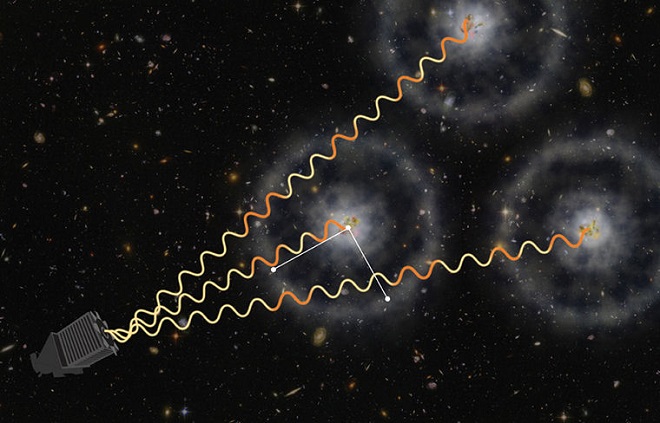

If two galaxies are on a collision course and eventually collide, they will merge into a single larger galaxy. At the centre of each galaxy is a massive black hole and they will also merge. But if gravitational waves have been formed in the process, spreading out into space, there might be a recoiling effect, so one of the two black holes is ejected. In some cases, the recoil effect is relatively weak and the black hole is pulled back to the centre. In other cases, the recoil effect is so strong that the black hole is flung out of the galaxy forever and remains isolated in the universe.

Black hole flung out of the galaxy

Astronomers have long been searching for such black holes that have been flung out of the galaxy by a recoil effect. Now they believe they have found such a black hole. It is located 90 million light years from Earth, which is relatively close for astronomers.

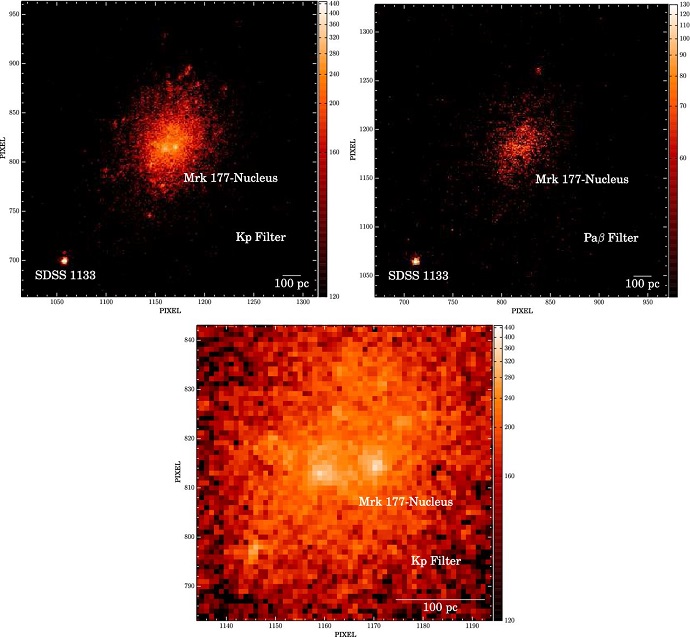

An international team of researchers led by Michael Koss, Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule, ETH-Zurich, along with researchers from the University of Hawaii and Allison Man from the Dark Cosmology Centre at the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen, have made observations at the Keck Observatory on Hawaii. The telescope is one of the largest in the world and using a special technique called ‘adaptive optics’, which can compensate for disturbances from the atmosphere, it is possible to obtain observations with incredibly high resolution.

“The observations show that the object called SDSS1133 still has a ring of dust and gas, which it is drawing inwards and engulfing as it emits radiation. The observations clearly show that there is no orbiting galaxy. By comparing the radiation from the object with the nearby dwarf galaxy Markarian-177, it appears that the black hole once belonged to the dwarf galaxy before it was flung out,” explains Allison Man, a PhD student at the Dark Cosmology Centre at the Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen.

The twin telescopes at Keck located on the summit of Mauna Kea in Hawaii. Each having 10-meter mirrors, they are currently the largest telescopes. The laser beam acts as an artificial guide star (shown in the picture) to correct for the blurring due to atmospheric disturbances, a technique known as adaptive optics for high-resolution observations. (Credit: Paul Hirst)

Possibly a starburst

Another possibility is that the object could be a special type of supernova, that is, an exploding massive star. When massive stars die, they explode and can form a black hole. The astronomers found photographs of the object from the 1950s and a supernova normally only lasts a few months, but it could be a case of a special massive star with a series of explosions that occurred at least 50 years before it finally exploded as a supernova in 2001. If this is the case, it will be one of the most energy-rich and sustained explosions of a star that has ever been observed.

In order to get closer to solving the mystery, the researchers will observe the phenomenon over the next year using the Hubble Space Telescope’s Cosmic Origins Spectrograph, which can study the spectral lines of highly ionized carbon in active black holes. The spectral lines from black holes are typically broad.

In a supernova, on the other hand, ionized carbon would only be produced right after the explosion and the spectral lines would typically be very narrow.

If this is a case of a supernova, the emission of light also quickly becomes weaker. If it is a black hole that has been cast out of the galaxy, on the other hand, it will emit light for a long time – perhaps millions of years.

Article in Monthly Notices, Royal Astronomical Society >>>

arXiv >>>